Kristin Ross’s The Commune Form traces a political tradition—based on reimagining class relations—that stretches from the 1871 uprising to the modern-day struggles of ZAD.

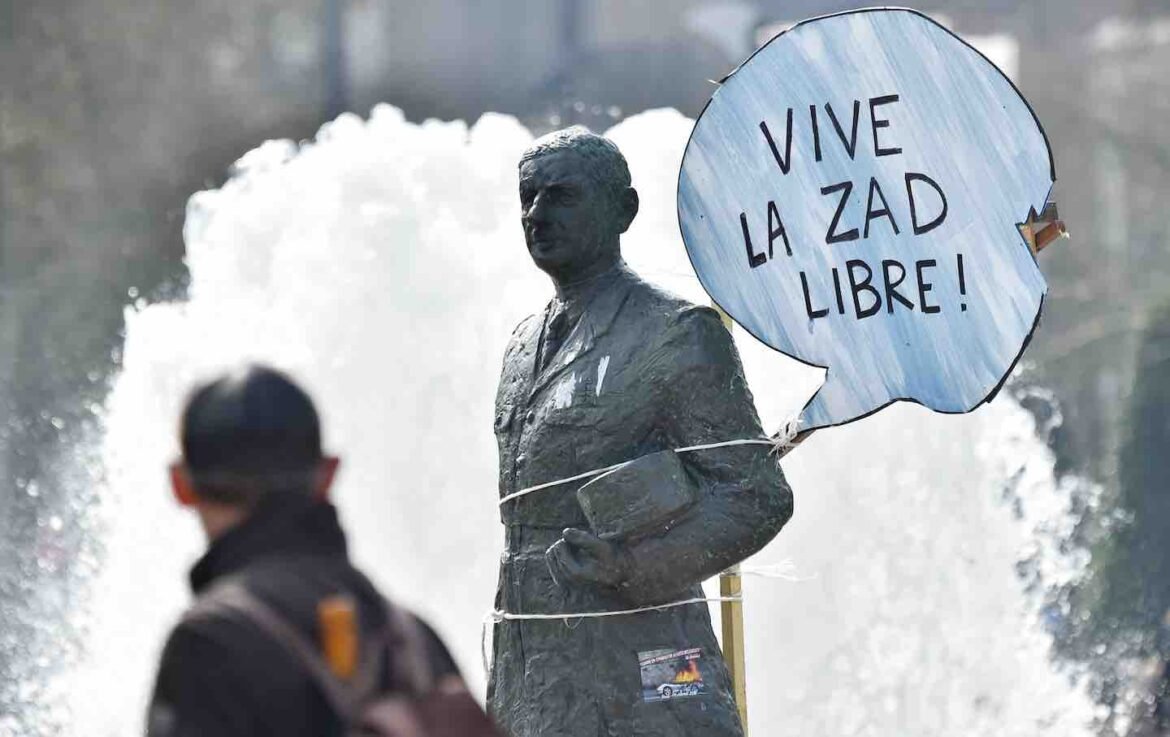

A man walks past a statue of Charles de Gaulle, with a cardboard speech bubble reading “LONG LIVE THE FREE ZAD” as hundreds of opponents to the Notre-Dame-des-Landes airport and ZAD activists gather to demand a collective management of the land planned for the airport’s construction, 2018.

(Photo by Loic Venance/AFP via Getty Images)

Wherever you go in this life, class society lurks at every turn. Our encounters with it often arrive in a minor key, the cracks and frictions that we meet with in the mundane aspects of our lives: the morning line for coffee, longer because the store is on a short shift as a result of corporate’s forays into union busting; the bus arriving late because of budgetary cuts in a city swarming with police; the rising rent and the luxury condos going up down the block. What may appear in isolation to simply be a mere frustration, an annoying hiccup, a minor sign of a world in flux, begins to appear in toto quite different as the asymmetries of power become so glaringly obvious.

Books in review

The Commune Form: The Transformation of Everyday Life

These banal outrages are entryways into the realm of the class politics we most often confront; they are sites from which we can begin to ponder who and what controls the levers of power in our daily lives, and as such they are crucial openings. Everyday life is where revolution is both first imagined and first lived. If, as Theodor Adorno famously stated, “wrong life cannot be lived rightly,” then to begin to reimagine everyday life and its contours anew can be a powerful ground from which to try and build new worlds that we can inhabit not in some distant future but now—a preparation for the future by way of collective political struggle in the present.

Kristin Ross stands as the foremost thinker in the legacy of what Henri Lefevbre called the “critique of everyday life,” and in her latest work, she proposes that the practices for remaking our social world rest within taking up and reviving the anarchistic and communistic tradition she calls “the commune form.” Ross begins, of course, with Karl Marx on the Paris Commune of 1871, that moment when the revolutionary Communards built an actually existing new social and political organization for a little over two months before being slaughtered by the revanchist forces of the French state. The Communards’ brief achievement, though, fulfills the essential baseline of what Ross describes as “people living differently and changing their circumstances by working within the conditions available in the present.” During the Paris Commune’s short life, its participants began to disassemble the functions of the state bit by bit and take up the tasks of politics themselves via direct association and mutual cooperation. Ross, like Marx, is less concerned with the Commune’s legislated achievements, such as the abolition of night work for bakers and the halting of rent collection, than the fact that its very existence for the first time demonstrated how laborers emancipated from their need for a wage would go about creating and managing the conditions of their lives. The improvisations of the Communards brought forth freedom as a practice through which they could experiment with how a community might choose to live together sans bosses and sovereigns.

This initial looking to 1871 is well-trodden ground for Ross, whose Communal Luxury: The Political Imagination of the Paris Commune (2016) sought to capture how the Communards created the conditions for all manner of radical poiesis, for aesthetic mergings between everyday life and new systems of value disconnected from capitalist forms, developing a vision of what she refers to as “communal luxury.” Ross therein claimed that “finding criteria for wealth that was distinct from the quantitative race toward growth and overproduction was the key to imagining and bringing about social transformation.” In the same manner that her earlier book oriented itself not only toward the afterlife of the Commune on the socialist and communist left but also within the anarchist imaginary, The Commune Form immediately supplements Marx’s reading with that of Pyotr Kropotkin, who saw in the Paris Commune a revitalization of an older tradition—the peasant revolts of the French Revolution, which had sought to bring about the restoration of feudal lands to the peasantry. “It was toward the possession of land in common that eighteenth-century revolutionary thought was focused,” Ross writes, before crucially adding a parenthetical aside: “(The same, I might add, could be said of our own time.)” In connecting the tradition of the rural struggle for the commons to our present—of climate breakdown, world-bestriding corporate monopolies, and heightening inequality—Ross’s study of the commune form from the 1960s until the present day points us toward a mode of political activity that seeks to defend against capital’s ecocidal drive by fighting to reclaim and defend the fundamental wellspring of human life itself. In so doing, she looks not to contestations over wages and working conditions on the shop floor, but rather to collective attempts to remake everyday life from (literally) the ground up—attempts that, like their predecessor in 1871, seek to break with the state and the wage relation altogether.

“The commune form, as form, does not lend itself to a static definition, unalterable through time,” Ross writes. It is neither a prewritten script from the past to be followed nor some idealized notion of a society to come. Instead, the commune form is identifiable only within the sites of actual social movements that have sprung forth to resist the capitalist conditions of a particular time and place. This fundamental elasticity of the form allows it, first and foremost, to adapt to the immediate and practical concerns of its participants. Ross argues that we must look to the specific historical examples of its emergence in land-based struggles that sought to defend a space and its occupants from the deleterious encroachments of the state and capital—invasions made, more often than not, under the banner of “development.” In Ross’s formulation, land is what allows the commune form to survive by providing the productive base from which its participants can reproduce themselves and their fight.

She looks, for instance, to the establishment of what has come to be known as the Nantes Commune in May 1968, a brief few weeks in which paysans (small farmers), students, and workers came together amid the wildcat general strikes occurring throughout France during that period to create what Ross calls “a kind of parallel administration for the purpose of satisfying the city’s basic needs” despite the suspension of public services. Their agitation, Ross argues, was rooted in something philosophical as much as it was material: a dissolution of the divide between urban and rural, industrial worker and agricultural producer. As the aerospace workers at Sud-Aviation outside Nantes went on a wildcat sit-down strike (the spark that led to more than 10 million workers across the country striking that month), the local paysans went into action. Utilizing the networks of mutual aid they had long since employed during periods of dire dearth, they began to distribute food to the striking workers’ families at cost or, at times, for free. The wives of striking workers organized a meeting among themselves, met with the strike committee, and then contacted the local paysan syndicates, who alongside the workers and students set up their own food distribution networks, cutting out the middlemen distributors entirely. Like the Communards in Paris almost a century before them, they began to produce for communal use. Newly created neighborhood associations could begin to act in the stead of the government as they coordinated “new methods of managing kids, garbage, fuel, and food.” Short-lived though it may have been, the Nantes Commune demonstrated the revolutionary prospects rooted in the coordination of urban revolt with rural paysans, who provided access to the raw materials necessary for preserving life during a revolutionary moment.

The central example of Ross’s new book comes in what emerged from the paysans’ efforts: the ZAD (Zone to Defend, an inversion of the French state’s Zone of Deferred Development) at Notre-Dame-des-Landes, where squatters-cum-communards occupied territory intended for the construction of an international airport, a fight that began in 1974 and then ratcheted up in the early 2000s, as developers began a more concerted push to finally evict those seeking to build new ways of life on these 4,000 acres, which were to be cleared of their farms and inhabitants. The communards would finally declare victory against the development project in 2018, when President Emmanuel Macron announced that the long-planned airport would not be constructed; indeed, even as the French state initiated a large-scale and violent eviction campaign later that year in reprisal, many of the participants still managed to hold out and hang on to the community that had been built over the decades of resistance.

The commune form as one that coalesces in defense ties sites like the ZAD to earlier struggles against an airport development by farmers and radical students in the Chiba Prefecture of Tokyo in the 1960s; in the Larzac in France in the 1970s; and in the United States, at Standing Rock in the 2010s and in the current fight against Cop City in the Weelaunee Forest in Atlanta. Just as Kropotkin saw the origins of the Paris Commune as possessing roots in ever-earlier forms, so too does Ross position these battles for the reclamation of everyday life—that which we can ourselves control and begin to shape anew in common with one another—as rooted in the ever-present legacy of 1871.

In Ross’s argument, the commune form springs up in defense against capital’s incursions upon the land because the land itself is capable of producing new ways of living that are fundamentally opposed to capital:

Land and the way it is worked is the most important factor in an alternative ecological society. Capital’s real war is against subsistence, because subsistence means a qualitatively different economy; it means people actually living differently, according to a different concept of what constitutes wealth and what constitutes deprivation. It is oriented toward the intrinsic value and interest of small producers, artisans, and paysans. It involves the gradual creation of a fabric of lived solidarities and a social life built through exchanges of services, informal cooperatives, cooperation, and association. It seeks to expand the spheres of activity in which economic rationality does not prevail. It means a life that is not molded and shaped by the world market, a life lived on the outskirts of the world organized by state and finance. These are the outlines of the commune form.

Ross’s most important contribution in this work is her vital insistence that many on the left today have, to our detriment, focused almost exclusively on the terrain of the urban and the workplace rather than upon the rural and the totality of everyday life outside the confines of the workday. For, as Ross insists, it was the enclosure of the commons and the displacement from the land that began the primary processes of capitalism as such, transforming all those expelled into the earliest progenitors of the urban, industrial proletariat. It is this primary alienation that has only grown across the centuries as we have become ever more divorced from the very source of our caloric intake, the most basic means of our survival. Ross forcefully contends that our collective flourishing, the expansion and revitalization of the commune form, depends first and foremost upon refusing to let this alienation fester any longer—upon returning ourselves to the land as the primary grounds for our political struggle against those forces of capitalist production that are ever more exhausted because they have exhausted so much of the earth itself.

In her own description of her time at the ZAD, Ross writes of how time seemed to shift: the recognition firsthand of a great truth about the commune form, that “time can be sold, but it can also be lived.” Time, like the land, can be reappropriated. Ross’s arguments will surely be subject to critiques insisting that this focus upon a return to the land is merely a palliative dalliance with romantic and pastoral dreams, like those of so many revolutionaries who failed to see the revolution they expected arrive in the urban core. Yet Ross makes the express case that the reclamation of the land is in fact the most practical of all solutions to our current conjuncture. As she puts it, “The world’s resources, like the rich endowment provided by past creative labor, are common property and should be managed and cared for collectively.” We are in a trap of economic rationality that has transformed the source of our sustenance into a site for ever more extraction and exploitation. The Commune Form maps a route by which we can begin to reclaim this common inheritance, before we find that it is forever lost.