How Fiorello La Guardia and a popular front of radicals and reformers transformed New York City

How the popular mayor and a popular front of radicals and reformers transformed New York City

Mike Wallace’s Gotham at War is the third and final volume of the most ambitious—and probably the lengthiest—work ever produced about the history of a single American metropolis. The first, simply titled Gotham, came out in 1999 and was cowritten with Edwin G. Burrows. More than 1,000 pages long, it began with the fateful meeting on the island of Manhattan between Lenape natives and Dutch colonists early in the 17th century and concluded with the merger of the five boroughs into a single “supercity” in 1898. It won the Pulitzer Prize for history.

Books in review

Gotham at War: A History of New York City From 1933 to 1945

Wallace then took 18 years to produce a sequel. Greater Gotham’s time frame was far more modest than its predecessor’s. Writing solo this time, Wallace zeroed in on the two decades between 1898 and the end of World War I. But like the first book, Greater Gotham contained multitudes, with fascinating chapters on everything from the subway, housing, and the Bronx Zoo to vaudeville, feminism, and child labor.

While not neglecting tales of social and cultural life, Gotham at War focuses more on the eruptions from elsewhere that shook and remade New York City. It begins in 1933 with a Brooklyn-based boycott of goods made in Nazi Germany and concludes with the decision by United Nations delegates to make the city their permanent headquarters. Like the previous volumes, its achievement lies not in its interpretive framework but rather in the wealth of detail that Wallace discovers and rolls out in a style both vivid and precise.

Taken as a whole, this grand trilogy represents an unstated tribute to the new social history, or “people’s history,” that became popular beginning in the 1960s. Now 83, Wallace was one of the founding editors of Radical History Review, the journal that helped to pioneer this emerging genre of scholarship. He had studied with the Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Richard Hofstadter when getting his PhD at Columbia. But like many of his New Left peers, he grew frustrated with the kind of consensus political history that was being written by liberals like his adviser, which then dominated scholarship about the American past.

Wallace wanted to write a history of the United States that foregrounded the experience of people often left out of traditional accounts: its radical and reform activists, its workers and immigrants. But he also believed it would be a mistake to write solely about ordinary people. “I don’t think you can do history and call it history and call it radical if you only look at radicals, the downtrodden trodding up,” he observed in a New York Times interview later in life: One also had to write about the elites who built and ran the structures of the economy and state that did much to keep “the people” down but that also sometimes aided their ascent.

Wallace and Burrows had originally set out to explore this rich history on a far grander geographic scale, with an examination of capitalism in the entire nation. “We had written hundreds of pages, but had barely gotten out of the 17th century,” Wallace recalled. And so “that’s when we decided to make it more manageable and tell the story through New York City.”

The new volume offers a compelling look at the way a big city’s economy functioned in an age of global war. Wallace describes how women broke through numerous glass ceilings: wielding tools in shipyards and munitions plants, driving taxis, and clerking on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange. He notes the subterfuge required to create a new weapon of mass destruction that would transform war forever: an office on lower Broadway served as the first headquarters of the top-secret program to build an atomic bomb. The enterprise was soon moved to other spots on the map, but it remained known as the Manhattan Project, “a false front” to confuse the enemy.

He makes room, too, for sketches of how New Yorkers managed to have a damn good time despite, or even because of, the momentous conflict that none could ever truly escape. The hit musical Oklahoma!, Wallace points out, was the work of two “fighting liberals” raised in New York, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, who presented “a prelapsarian vision of a time when social tensions had (supposedly) been subsumed in the name of patriotic comity.” Bebop jazz, Afro-Cuban dance music, and cheap paperbacks also proliferated, as did the frantic eroticism of an old Times Square where hordes of young people, in and out of uniform, came looking for hookups and usually found them.

With his omnibus method, Wallace sometimes strains to make a New York connection to every national development that took place in the era. But he does document a wealth of fine ones—from the New York roots of the Popular Front to the story of those Gothamites who led the long and successful battle to tear down the color line in professional baseball. He introduces Lester Rodney, sports editor of The Daily Worker, who ran countless pieces advocating the integration of baseball, and describes how Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and two leftists, US Representative Vito Marcantonio and City Councilman Benjamin Davis, demanded investigations into the persistence of Jim Crow on professional diamonds. Finally, the same month that Japan surrendered in 1945, the Brooklyn Dodgers signed Jackie Robinson to a minor-league contract.

Wallace would not have devoted so many years and so many pages to the Gotham trilogy if he hadn’t been guided by a great love for the city. He has a particular fondness for anecdotes that beam with an aggressive insouciance familiar to any lifelong New Yorker. Midway through the current volume, he tells of a German U-boat captain who had sunk many Allied ships in the Atlantic. One night in 1942, the captain’s U-boat surfaced off the coast of Brooklyn, seeking another kill:

At 10:00 p.m., just below Coney Island, he paused on the city’s very doorstep, gazing in amazement at the Ferris Wheel and the Parachute Jump highlighted against the blazing backdrop of light thrown up from incandescent Manhattan. The captain was mesmerized, and also irritated at the arrogance implicit in the luminous spectacle. Recalling blacked-out Europe, he jotted in his war diary: “Don’t they know there’s a war on?”

No one has ever known the history of New York City better than Mike Wallace or told it so well. Barring a total surrender to AI, I bet no one ever will.

At the center of Gotham at War are two stories that initially appear to be at odds. On the one hand, Wallace wants to dispute the comforting myth that, during the bloodiest war in history, America’s “greatest generation” put aside its many differences and united on the home front to destroy the twin evils of European fascism and Japanese militarism. In abundant and often captivating detail, Wallace shows the opposite: He describes the multiple battles among New Yorkers that raged before Hitler invaded Poland in 1939 and continued until the horrific conflict finally ended and the Cold War began. He tells about those New York City radicals, liberals, and conservatives who argued furiously about whether to enter the war at all. He examines how, after the attack on Pearl Harbor, African Americans protested passionately against their de facto segregation from good jobs and decent housing, while pacifists demanded a negotiated peace instead of unconditional surrender. He describes how some of these conflicts between New Yorkers turned violent, as when pro-Nazi thugs beat up Jews at random and vandalized synagogues in northern Manhattan.

But the book tells a story of unity as well. Charting the formation of the Popular Front in New York, Wallace chronicles how an alliance of liberals and radicals was able to manage these discontents and govern the city with support, grudging or not, from most of its people. This coalition included socialist union leaders like Sidney Hillman (who organized the first political action committee) and Adam Clayton Powell Jr., the eloquent Black councilman and minister whose weekly paper often echoed the views of the stalwartly anti-racist Communist Party. The message of wartime solidarity, Wallace notes, was also promoted by “fighting liberals” from the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr to Walter Winchell, a widely read columnist with a popular radio show who “linked domestic right-wingers to fascists abroad.”

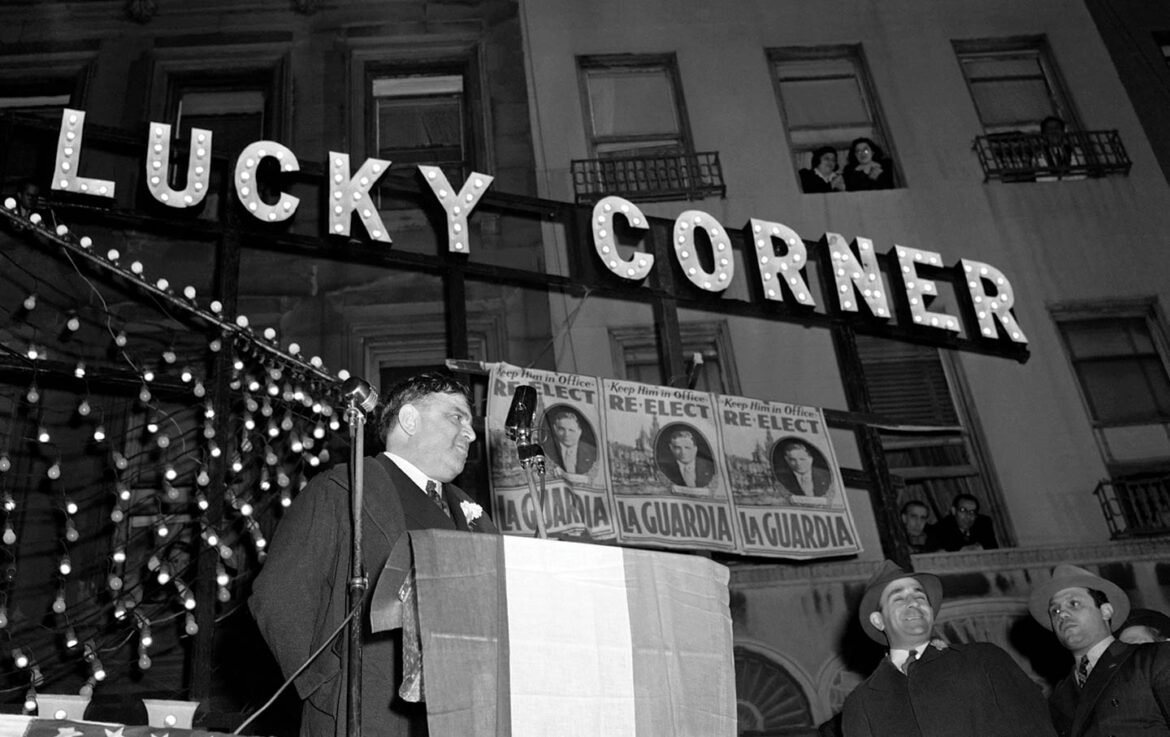

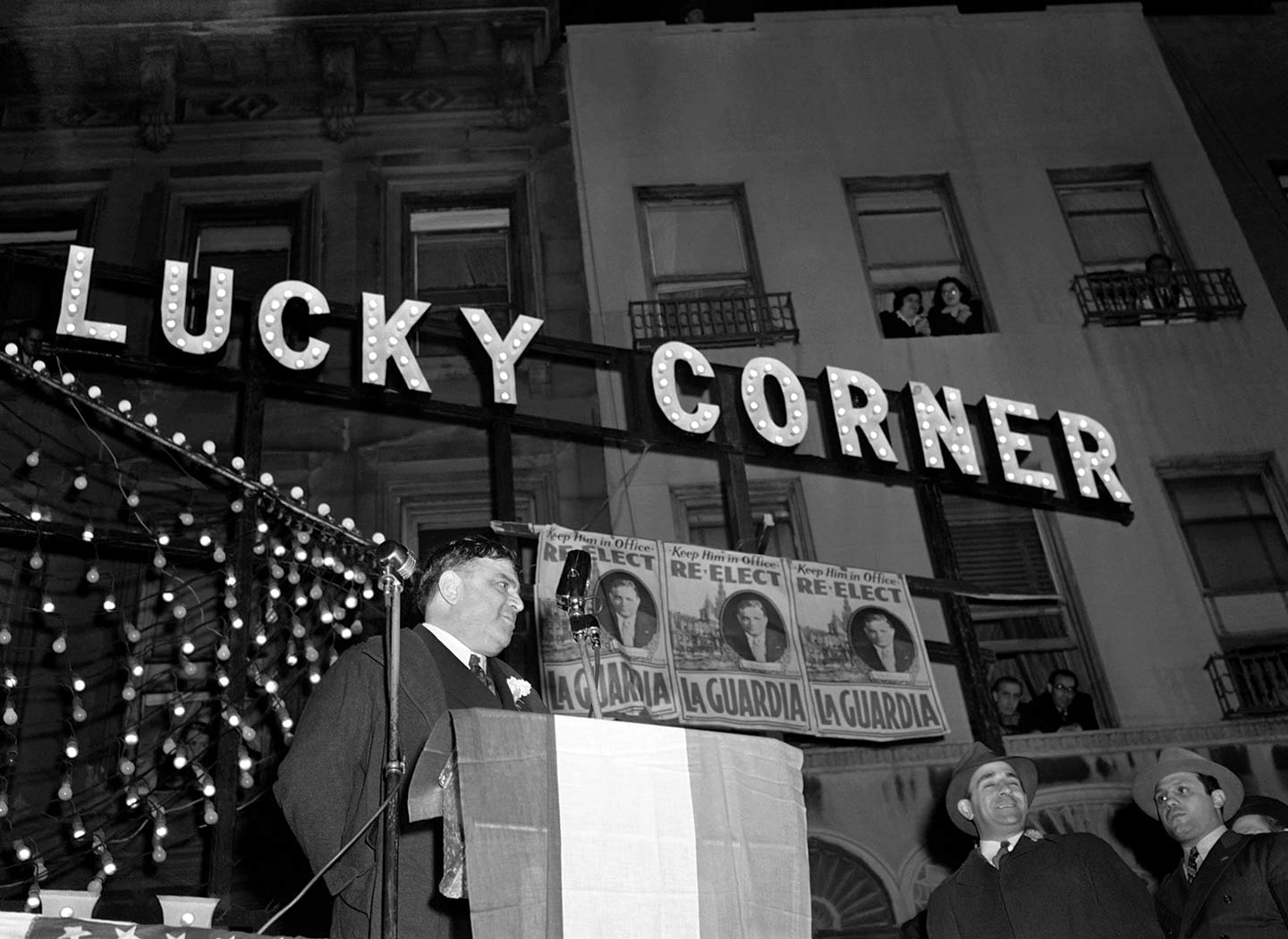

Throughout most of the 1930s and the entire Second World War, two New York politicians of rare skill and charisma headed up this coalition: Fiorello La Guardia and Franklin Roosevelt. La Guardia served three terms as mayor, during which his administration created the institutions of a nascent social democracy, from public housing to plenty of playgrounds to the nonprofit City Center of Music and Drama. Fluent in Italian and Yiddish, the flamboyant city executive once conducted the New York Philharmonic and took to the radio during a newspaper strike to act out cartoons that the city’s children would otherwise have missed. Roosevelt, a former New York governor, was a close ally; throughout these years, he funneled thousands of jobs to city residents. His genial populism also won over tens of thousands of working-class New Yorkers who in other settings might have been divided along ethnic, religious, and political lines.

In many ways, La Guardia and Roosevelt made an odd couple—at least at first. The son of European immigrants, La Guardia was a progressive Republican with socialist sympathies, while Roosevelt came from a wealthy and influential family of conservative Democrats. He’d grown up on an estate north of the city, near the Hudson River, that featured a stable and a horse track. Yet the two men shared the desire to forge a coalition that could narrow the gap between social classes by enacting policies that favored the needs of working people over those of the “economic royalists” who, Roosevelt asserted, “had reached out for control over Government itself.”

In New York City, La Guardia funneled money to big municipal construction projects (including the airport that bears his name), encouraged labor organizers, and expanded public housing. He was also an unyielding foe of fascists both at home and abroad. Down in Washington, FDR and the Democratic Congress passed similar measures, although the president failed to convince lawmakers to repeal the embargo against sending arms to nations threatened by the rise of Hitler and Mussolini until World War II began. But before the US entered the war, Wallace writes, “Roosevelt and his New Deal comrades had…planted a standard—a left-liberal ensign, blazoned with the colors of social democracy and antifascism—to which a critical cohort of like-minded New Yorkers would now repair.”

The local government that flew this flag embodied a popular vision of cultural tolerance and a politics aimed at providing a decent life for all. But it was something of a vanguard at a time when Jim Crow, antisemitism, and libertarian economics still held sway in many cities and states. As early as 1936, a Russian-born novelist just starting out as a popular crusader for untrammeled capitalism grouched to a friend, “You have no idea how radical and pro-Soviet New York is.” Her name was Ayn Rand.

The story of how the Popular Front, led by the mayor and his good friend in the White House, dominated public life in New York drives the narrative of Gotham at War. Wallace rarely describes any aspect of daily life unless it bears on that larger drama. He says almost nothing, for example, about how ordinary, non-activist New Yorkers survived the Great Depression, and little about how they experienced the Second World War.

One of the book’s more poignant images is the close-up of a newsstand and its doleful operator, snapped the day after Roosevelt died in April 1945. The photo, published in Look magazine, was shot by Stanley Kubrick, then a 16-year-old Jewish kid from the Bronx. Alas, the middle-aged fellow in a cloth cap and wrinkled tweed jacket glancing at the headlines remains anonymous. It’s a metaphor of sorts for Wallace’s attention to the big changes that rocked the city in these years more than to the working folks who were often protagonists in the narratives told in the first two volumes of his landmark history.

All this took place in a metropolis as critical to the war effort as any in the nation. Over 10 percent of the city’s population—736,000 New Yorkers—joined the armed forces. The city’s myriad small factories turned out a cornucopia of military goods, ranging from periscopes for submarines, to penicillin and meals for GIs, to napalm, the fiendish liquid that burns skin to the bone. “Wartime Gotham remained by far the largest manufacturing center in the nation,” Wallace reports, “unsurpassed in diversity of industries, number of factories, and aggregate volume.”

In telling these stories, Wallace makes no attempt to hitch all his mini-narratives of industry, local discord, and politics to a grand interpretation. Instead of an explicit thesis, Gotham at War takes an ultra-empirical approach. Wallace assembles a huge collage of individuals and organizations, events and businesses, to suggest his view of what occurred and why, but without announcing a larger meaning to the grand story he is telling. On this massive canvas, he also pastes lyrics from popular songs, emotional images from war posters and comic books, and a grab bag of surprising statistics.

Did you know, for example, that nearly 40 percent of the Chinese Americans in New York City were drafted? Exclusion acts passed earlier by Congress kept Chinese men from building families that would have exempted them from the draft. Wallace also notes that, in the middle of the Great Depression, the posh and venerable Union Club offered its wealthy members “a choice of thirty dishes for breakfast, any of which could be served in bed.”

Without a big idea to guide readers through more than 800 pages of text and illustrations, Wallace relies on his unparalleled knowledge of every significant aspect of the city’s past to entice those readers to keep turning his many pages. Because he writes with wit and flair, one seldom regrets the absence of a larger argument.

Analogies between the political scene that Wallace describes and the one that exists in the city today come naturally to mind. The specter of fascism looms at home now instead of abroad, but New Yorkers elected a dynamic young socialist as their mayor. Like La Guardia, Zohran Mamdani won by building a multiethnic coalition of liberals and radicals and gained the support of most unions. He has ambitious plans to provide low-cost housing and to raise wages for the many and taxes for the wealthy few. And his charismatic ebullience makes it hard to portray him as someone out to punish those who disagree with his policies.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Still, no mayor of New York can be entirely or perhaps even mostly the master of their own fate. La Guardia easily won all three of his elections. But in 1945, with both New York’s economic future and a fourth personal victory uncertain, he declined to run again. And even if had run again and won he would no longer have been certain that the money he had promised to repair and expand the city’s infrastructure would be available. The federal government would have supplied most of the funds, and with the war over and FDR in his grave, the Little Flower sensed that was not going to happen.

With the Republicans in charge of the presidency and Congress, Mamdani will not be able to turn to Washington as La Guardia did during the New Deal. The surprising warmth Trump expressed when they met in November will likely cool once the mayor tries to implement policies that conservatives in and away from Gotham will hate. And there won’t be a global war to persuade a majority of New Yorkers to rally against a common enemy determined to humble or destroy them. One can only hope that, as with La Guardia’s election in 1933, his victory will be the harbinger of a progressive surge in the rest of our country.

From Minneapolis to Venezuela, from Gaza to Washington, DC, this is a time of staggering chaos, cruelty, and violence.

Unlike other publications that parrot the views of authoritarians, billionaires, and corporations, The Nation publishes stories that hold the powerful to account and center the communities too often denied a voice in the national media—stories like the one you’ve just read.

Each day, our journalism cuts through lies and distortions, contextualizes the developments reshaping politics around the globe, and advances progressive ideas that oxygenate our movements and instigate change in the halls of power.

This independent journalism is only possible with the support of our readers. If you want to see more urgent coverage like this, please donate to The Nation today.

More from The Nation

The Puerto Rican artist’s performance was a gleeful rebuke of Trump’s death cult and a celebration of life.

Black and trans drag performers are crowdfunding to survive in one of the most expensive cities in the world.

The president has gone after us because of who we are and what we value. We have an obligation to resist.

The medspa industry is moving more quickly than we can keep up with. Meanwhile, women are being told that if we don’t too, we will lose our cosmetic capital.