Black and trans drag performers are crowdfunding to survive in one of the most expensive cities in the world.

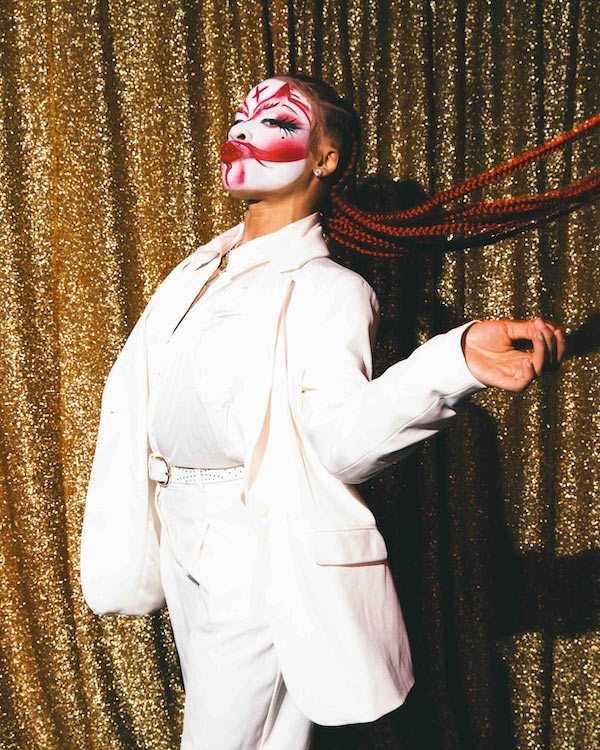

After he somersaults on the bar in six-inch stilettos and a blood-stained, Chucky’s-bride-themed white corset, the crowd at Bushwick’s queer-owned Pink Metal Bar roars in delight for Xaddy Addy, a Black transmasculine drag king and sideshow performer. The audience has gathered in the intimate bar for Superstar Open Set’s Halloween show, an open stage that Xaddy Addy cohosts each week alongside drag performer Pachacvnti. After a night of performances from Brooklyn’s emerging talent, the crowd remains spellbound as Xaddy Addy staples cash tips to his cheeks, thighs, and hips. Not even the loud cheering drowns out the clack of the staple gun as it pierces his skin. His self-assured, “weird” drag performance—an expansive genre melding drag with horror, stunts, and complex dramaturgy—belies the economic insecurity and discrimination he faced while building a following.

Manhattan native Xaddy Addy tells me that drag was “a way to save his life” after years of doing sex work “100 percent out of survival.” For many, drag is both a calling and an art form—one that contributes to New York’s $35 billion nightlife economy. But income from their performances barely covers their bills in one of the most expensive cities in the world, where the average rent soars beyond $3,000. Many Black and trans performers are crowdfunding on social media to cover rent, medical bills, and groceries.

“You have some of the best Black trans drag performers in the world in your city,” says Klondyke, a Black drag artist and sideshow performer. “Why are they starving? Why am I seeing more people that are Black and trans posting mutual aid than posting shows that they’re in?”

With the election of Mayor Zohran Mamdani, drag artists are hopeful about his promises to make the city more affordable, by freezing rent for stabilized housing, and to expand protections for trans New Yorkers. But they argue that policy changes alone will not be enough to undo decades of decisions that have disenfranchised the city’s marginalized residents. That will take all of us.

Drag performance artists occupy a precarious ledge in New York’s gentrified landscape. The city’s exorbitant costs of living, along with Trump’s despotic policies, have caused residents and tourists to opt out of live entertainment. “I can’t tell you how many shows I’ve been a part of that have been well promoted, the promo’s gorgeous, the cast is posting, the tickets are not too expensive,” Bri Joy, a drag king and go-go dancer, says. “All the conditions are correct for a beautiful day at the beach, and then no one shows up at the beach.”

But Black and brown artists have faced decades of discrimination over the years, long before Donald Trump kicked off his crusade against trans people. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Afrosephone, a showgirl from New York, remembers, “the girls and the dolls went to work” across swaths of Manhattan—from the West Side Piers to the iconic La Escuelita on West 39th Street. By contrast, white venues permitted Black or Latine people only on designated nights. These clubs “were a thousand times worse back then,” Afrosephone says, “where they could be openly racist to you.” Black and brown artists forged their own spaces underground, and their contributions to nightlife attracted tourists, a new generation of queer transplants, and, inevitably, the cops.

In response to the proliferation of underground clubbing, former Mayor Rudy Giuliani disproportionately raided Black and brown clubs for dancing, smoking, or playing loud music. He also wiped the dust off the Prohibition-era Cabaret Law, which outlaws dancing in venues without a pricey cabaret license. Giuliani’s policies, ostensibly aimed to reduce crime, sought to attract wealthy transplants and business owners to the city. Mayor Mike Bloomberg continued these draconian measures into the early 2010s. A long battle with the NY State Liquor Authority ended in La Escuelita’s untimely closing in 2016, only a year before Mayor Bill de Blasio finally repealed the Cabaret Law.

The NYPD’s crusade on Black and brown clubs robbed performers of cultural sanctuary and employment options. Real estate developers and culture-hungry newcomers flocked to pick at the ruins. Venue owners and event producers shut Black performers out of regimented clubs, where partygoers shuffled into VIP sections, hardly danced, and snapped photos of ostentatious bottle service. Today, Black and trans artists continue to face discriminatory hiring practices.

Bri Joy says that many promoters adhere to the “paper bag test”—if a drag performer’s skin is darker than a paper bag, then they’re turned away from certain clubs. Trans artists face compounded scrutiny from audiences and other drag performers, who have asked Bri Joy probing questions like “What kind of trans are you?” and outed Afrosephone on stage without her consent.

“Even now, especially in Manhattan, there can only be one or two top Black performers at a time,” Afrosephone says. “We’re at the mercy of these establishments that don’t truly want to work with us.”

Mayor Bill de Blasio’s relatively progressive policy decisions led to ephemeral gains for drag artists. Along with expanding labor rights and housing protections, de Blasio founded the Office of Nightlife (ONL) to support workers and local business development after dark.

When Covid restrictions were lifted in 2021, Klondyke recalls that “a lot of corporate and white money” was being “thrown at drag” programs. Diverse drag lineups attracted audiences who toted stimulus checks and a nascent, if not fleeting, solidarity with people of color after the Black Lives Matter movement of 2020. “I was doing at least three or four shows a week for over a year, and that was able to sustain me,” Klondyke says. “Then it just starts to fizzle.” Once the news cycle closed the chapter on racial justice, so did the city’s doors and wallets.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Eric Adams pledged to revive the nightlife economy when he was elected mayor in 2022. During his term, he frequently appeared at swanky Midtown venues where he dined on branzino with his inner circle, including convicted fraudsters and former Governor Andrew Cuomo—whose tenure saw steep increases in housing costs and a decline in the number of Black residents.

The New York City Council sued Adams for blocking legislation to offer more housing vouchers and recently overruled his proposal to hike Section 8 rents. His $650 million campaign to combat street homelessness raises questions about the plan’s execution, given that his former policies led to increased policing in subway stations and forced displacements of unhoused people.

Adams, to his credit, led the transition from Giuliani’s authoritarian MARCH program, in which police cracked down on clubs without warning, to CURE, an initiative that mediates nightlife violations before resorting to harsh police enforcement. While these measures bridge the gap between city government and nightlife venues, Adams’ administration failed to meaningfully address the most pertinent threats to nightlife workers: housing insecurity and finding safe, steady work.

“There have been one or two times where I’ve had a bout of unemployment and I’ve tried to make it work with just nightlife,” says Bri Joy. “I owed so much back rent and I was the brokest I’d ever been in my life. It was the first time that I’d really seen my account hit actual zero.”

Even New York’s “Freelance Isn’t Free” law, which protects freelancers’ rights, requires written contracts only for projects of $800 or more with a single employer. But underground drag artists often earn up to a couple hundred dollars from gigs, if they’re paid at all, and recurring bookings are difficult to come by. In August 2024, the ONL reported that its efforts to expand affordability for DIY spaces were “currently on hold”—despite the fact that increased access to venues would help drag performers and producers like Vague Static create more employment opportunities.

“It’s gonna be a lot easier a lot of the time for a white producer to get into the clubs, to produce a thing, and pay the people,” says Vague Static. They are a co-organizer of Lil’ Park Drag Show, a free program that took a hiatus this year following a spike in transphobic safety threats. “I do not have the money to pay the people for their time.”

A 2019 ONL study reports that income stability and gig competition pose substantial hurdles to 80 percent of nightlife entertainers, and drag is especially cutthroat. Individualism, prejudice, and poor conflict resolution within the drag community—even among other LGBTQ+ people of color—widen the gaps of public policy failures.

Drag kings in particular are disregarded and underpaid compared to drag queens and well-known entertainers, who use “words like community and friendship to get close to you,” only to disappear when they find “a better booking,” according to Klondyke. These discrepancies have material consequences. In January, after Klondyke failed to secure consistent work and accumulated $10,000 in unpaid rent, his landlord evicted him and his partner from their Brooklyn apartment. “Our income is very sporadic,” reads Klondyke’s fundraiser for housing costs. “We are at the end of our rope.” Although Klondyke began fundraising in 2024, his campaign is still less than halfway to its goal, and his search for secure housing wears on.

“When you become silent, you fall into the similar categories of the rising conservatism that we see in this country,” Xaddy Addy says. “People are left to feel alone and invisible and think to themselves, what does it even mean to be in these spaces? What does it even mean to exist in this life?”

For as long as Black trans artists have existed in New York City, they have addressed their uncertain living situations with community-based solutions. In 1968, drag queen Crystal LaBeija created the House of LaBeija—an artist-led collective that offered mentorship and support networks to Black trans talent—to resist the racial discrimination she faced in ballroom pageants, where women of color lightened their faces to compete for white judges only to lose to non-Black talent. LaBeija’s house system was the first of its kind, not only launching drag to international acclaim but offering a blueprint for how drag artists can support each other in moments of need. “There would be no ballroom or drag culture without Crystal LaBeija,” says Afrosephone.

During the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, performers relied on drag collectives, where drag artists shared costumes, exchanged industry knowledge, and hosted in-person events like “Takes the Cake,” “a drag competition for drag king, things, and other non-binary & queer performers.” Klondyke, who “came up in the time of collectives” and won Takes the Cake in 2021, recalls the electrifying presence these opportunities carried, “especially for kings and things,” who were “excited to have spaces to do our thing.”

The Cake Boys, the drag collective behind Takes the Cake, had to shutter their live event programming in 2024, but other underground initiatives have sprouted up to fulfill drag artists’ needs. More recently, Klondyke and Xaddy Addy cofounded Black Cherry Sideshow, the first-ever trans and BIPOC-led drag sideshow, alongside drag artists Selena Surreal and Oliver Herface. The quartet performs every second Saturday of the month at Purgatory Bar in Bushwick, where they engage in a dizzying range of stunts like eating fire, lying on beds of nails, and taking needles and mouse traps to their bare flesh. With an historic one-year anniversary event held last May on Coney Island, Black Cherry Sideshow dares to reimagine the sideshow not as an exploitative spectacle for white consumption but a way for trans performers of color to reclaim their power and, according to Xaddy Addy, “raise the stakes in my drag in a dangerous but safe way.” Along with his sideshow grind, both Xaddy Addy and Afrosephone host open sets to uplift up-and-coming drag artists, while others circulate calls for mutual aid.

“Being a drag performer, I’d much rather [use] art to fight through a fascist system instead of making art to appease a fascist system,” Klondyke says. “The fact that my art is able to exist as a Black trans person is what is political.”

Drag is inextricable from the city’s anti-fascist future. Zohran Mamdani’s use of relationship-building, volunteerism, and media to build power mirrors the tactics of Black and trans-led collectives throughout New York’s history.

So far, Mamdani has acted on some of his campaign promises and fallen short on others. Although Mamdani called to defund the “racist and anti-queer” NYPD on X in 2020, he roused criticism from progressives after choosing to retain Jessica Tisch, a moderate who increased surveillance across the city and opposes bail reform efforts, as the NYPD commissioner. The decision to maintain Eric Adams’s pro-NYPD appointment, along with his delayed, lackluster response to two fatal police shootings days into his term, cast suspicion over whether he’ll follow through on his pledge to protect New Yorkers who are most vulnerable to police violence.

He has made more hopeful strides in the realm of nightlife and entertainment, where he elected Freelancers Union leader Rafael Espinal as commissioner of the New York City Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment. Espinal led the charge to repeal the Cabaret Law and pass the Freelance Isn’t Free Act as a city councillor under Bill de Blasio. The native Brooklynite’s track record of inclusive policy reforms, along with his recent promises to expand affordability for NYC creatives, seek to meaningfully address the cost-of-living catastrophe that worsened under Adams’ administration.

Yet policy changes alone are never enough. True power, as Mamdani even emphasized on his campaign trail, lies in the hands of the people.

New Yorkers have a responsibility to show up and stand down for nightlife performers by attending drag shows run by Black trans performers, tipping and paying entertainers living wages, and advocating for inclusive hiring practices.

“You shouldn’t wait until somebody is on Drag Race to show your support,” says Afrosephone. “The one thing that will keep us performing, the one thing that will keep us afloat, is if you show up.”

From Minneapolis to Venezuela, from Gaza to Washington, DC, this is a time of staggering chaos, cruelty, and violence.

Unlike other publications that parrot the views of authoritarians, billionaires, and corporations, The Nation publishes stories that hold the powerful to account and center the communities too often denied a voice in the national media—stories like the one you’ve just read.

Each day, our journalism cuts through lies and distortions, contextualizes the developments reshaping politics around the globe, and advances progressive ideas that oxygenate our movements and instigate change in the halls of power.

This independent journalism is only possible with the support of our readers. If you want to see more urgent coverage like this, please donate to The Nation today.