What Zohran Mamdani’s win signifies—and what it doesn’t.

Muslim New Yorkers gather in Astoria, Queens, to celebrate Zohran Mamdani’s election victory on Tuesday, November 4, 2025.

(Lokman Vural Elibol / Anadolu via Getty Images)

In the early afternoon of November 4, Jackson Heights was no more abuzz than it is on any other day. The wind whipped Arepa Lady’s awning, two butchers pushed skinned goat carcasses across 73rd Street in grocery carts, and couples stopped at fuchka stands.

There was an election underway. New York City was seemingly poised to elect its first Muslim, South Asian, African-born mayor, Zohran Mamdani. And still, no one in this part of Queens seemed in any particular hurry. Inside Premium Sweets, when a customer asked the server if he had voted, he responded, “I’ll get there, I’ll get there. Polls close at 9, right?”

Zohran Kwame Mamdani is a Ugandan-born immigrant of Indian descent, raised Shia Muslim in an interfaith household in Morningside Heights. The novelty of his origins has broad appeal. As Zenat Begum, Brooklynite and founder of Bed-Stuy’s coffeehouse and community space Playground, put it, “He is a walking concoction of every New Yorker in one person.”

Still, one trait is all too familiar in this city’s political imagination—his Muslimness.

Perhaps that is why, in the final weeks of the New York City mayoral race, having exhausted all other tactics, Mamdani’s opponents turned to the tawdriest of anti-Muslim rhetoric. On a radio show, Andrew Cuomo chuckled at the suggestion that Mamdani might cheer for another 9/11. Mayor Eric Adams warned of a surge in “Islamic extremism” if he won. On the debate stage, Curtis Sliwa accused the Democratic nominee of supporting global jihad. Beyond his fellow candidates, US Representative Andy Ogles referred to him as “Little Muhammad” and tweeted footage of the 9/11 attacks under the caption “WAKE UP NEW YORK!

Equality Labs, a South Asian Dalit civil rights organization, tracked 1.15 million Islamophobic social media posts about Mamdani that were viewed over 150 billion times between January and October 2025—many of which referred to him as “terrorist” or “jihadist.” Islamophobia is at once a misnomer, suggesting irrational fear like the compulsive horror of bugs, and a tragically apt name for the permissibility of Muslim hate.

But New York City’s Muslim population is an immensely heterogeneous group within an even more diverse metropolis; it includes financiers and delivery cyclists, Senegalese and Indonesians, queer individuals and, yes, straight people too. And a lot of them don’t want to talk all that much about Islamophobia. On Election Day, I stopped outside PS 69, a Jackson Heights school doubling as a polling place. I asked Refaite Hossain, a member of the Jamaica Muslim Center, about his excitement around a prospective Muslim mayor. Hossain corrected me, “It’s not about his identity. He’s talking about working-class people.” When asked about the Islamophobic attacks levied against Mamdani, Hossain unintentionally yawned, and his eyes darted elsewhere.

If there is one tenuous commonality amongst Muslims I have noticed in the last two years, as genocides of predominantly Muslim populations continue unabated, it is this bored indifference toward Muslim hate, and a preference for humor in the face of absurdity. Shortly after Mamdani won the primaries, the Internet was set ablaze in sarcastic quips by Muslims. One X post joked, “SHARIA LAW IS COMING!!!!!”

In the late afternoon, Queens native Farzana came out to canvass for Mamdani in front of PS 69. Like Hossain, she focused on his track record over his faith: “My entire family and neighborhood are mostly taxi drivers. That’s their bread and butter. When he [Mamdani] put himself and his body on the line, he showed we mattered. How many elected officials have done that?” Farzana was referencing Mamdani’s 15-day hunger strike with taxi drivers in 2021 to demand debt relief. Andrew Cuomo clamored on about Mamdani’s inexperience, but did not account for voters who wanted a different kind of experience—the kind formed in the streets.

Before leaving Jackson Heights, I stopped by Kabab King, Mamdani’s self-declared favorite restaurant. As I waited for my beef Bihari on naan, a Pakistani waiter shuffled from the grill to the dining area, listening loudly to Urdu-language news. He reminded me of last summer, when Mamdani appeared on a Pakistani news show to speak to the Pakistani diaspora in New York about his campaign promises. Knowing that many South Asians tune in to news from back home more frequently than to local outlets, Mamdani stretched his campaign transnationally. He approached apolitical or disillusioned residents with dormant electoral power—many of whom, in a post 9/11 New York, happened to be long-ostracized Muslims.

As night fell, I left Queens for the Brooklyn Paramount Theater, the site of Mamdani’s election night watch party. There were news crews from around the world. I sandwiched somewhere between a Turkish channel and Spectrum News NY1, and scarfed my Bihari roll. I watched as the NYPD Counterterrorism Unit donned armor and accessorized with massive guns. It was bewildering to leave a neighborhood where everyone seemingly knew the Democratic nominee personally, and arrive in a place crawling with cops and cameras, where he had already become—win or lose—a resounding politician.

Upon entering the swanky, high-ceilinged venue, I spotted a mustachioed man at the bar alone. It took me a second to clock that it was Hasan Piker. He spun around and jovially asked, “You want an interview? Eighty thousand people are watching me live on Twitch, so go ahead.” We stood in the hallway under what one of his viewers called “bisexual lighting.” Piker exalted about Mamdani, “I have never been truly represented, and I don’t necessarily care to be demographically represented. I care more about the ideology of a person, the platform. But in Zohran, I got a twofer.”

Piker concisely captured the dual appeal of Mamdani for Muslims living in New York full-time (which Piker does not). Mamdani’s consistent messaging around affordability stood out after disillusionment with the Democratic establishment’s politics of idolatry—putting a premium on representation without transparent, people-focused policy would no longer have sufficed. Seeing oneself represented, not just demographically but ideologically as well, transforms a liberal indulgence into a democratic necessity—one that Muslim Americans, too, deserve to experience.

Around 9:30 pm, after the polls closed and before attendees could settle into the party, grab drinks or head to the VIP section—where I momentarily spotted Hasan Minhaj’s erect quiff—it was announced that Zohran Mamdani was the mayor-elect of New York City. He won with over a million votes, the largest voter turnout since 1969. The crowd erupted. In various corners, people began making calls. One uncle FaceTimed family in Egypt, Detroit, and Toronto. I sent my family a video of a silver-bearded elder moshing to “A Milli” by Lil Wayne for proof that the night was real. In triumph was a familiar immigrant impulse—to widen the circle, to invite everyone under the tent, to celebrate with strangers and family alike.

On my left, a middle-aged man yelled, “We did it! We did it!” to nobody in particular. This was Mouhamadou Aliyu, a member of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance who had participated in the hunger strike with then-Assemblyman Mamdani. He was looking around for someone to embrace, so I tapped his shoulder and we hugged. Tears filled his eyes as he beat his chest, “I put my life on the line for that man, and he put his life on the line for me!”

When we parted, over the cacophony of joy, Aliyu said, “It’s our—” and because I did not hear the end of his sentence, I responded, “Time?” in reference to one of Mamdani’s late-campaign slogans. To which he shook his head as if it being our time was too presumptuous. “Our chance!”

Many leftist Muslims I spoke to shared a similar sentiment to Aliyu’s—that “our time” implies yet another transfer of power—without viewing Mamdani’s win as a singular opportunity for critical reform. The real test for Mamdani begins now—will he protect immigrants hunted by ICE? Will he excuse the NYPD’s brutality and inefficiency? Will he abandon gender-affirming care? An activist based in Brooklyn told me, “Many of us spent the last two years protesting the genocide in Gaza, so we are already organized. We will exercise the same outspoken scrutiny towards the man who is now in charge, and I think he knows that.”

About an hour after his win, Zohran Mamdani took the stage with a freshly trimmed beard. In a departure from his usual levity, he delivered a decisive 20-minute speech. He repeatedly called out President Trump and even slighted his opponent by invoking “a great New Yorker,” Mario Cuomo. CNN’s Van Jones was dismayed by the “character switch,” in which Mamdani was no longer boyishly acquiescent. I was 20 feet away as he landed one zinger after another. I found myself glancing toward the left of the stage, where his 79-year-old father sat watching. Mahmood Mamdani named his only son after Kwame Nkrumah, the revolutionary.

If one looks at Mamdani’s father, one understands that Islam is not what frightens the Democratic old guard or Debra Messing about the mayor-elect. Mahmood Mamdani’s seminal Good Muslim, Bad Muslim dismantles the bifurcation of the “secular, Westernized” Muslim versus the “tribal” one. In unapologetically eating with his hands, despite a barrage of racist mockery, candidate Mamdani exemplified his father’s scholarship. In Neither Settler nor Native, a book dedicated to his son, professor Mamdani explored the “permanent minority,” a group excluded from exercising political power due to enduring colonial legacies. As Asad Dandia, a public historian of New York and informal adviser in Mamdani’s personal Kitchen Cabinet, explained to me later: “It’s a book that grapples with how to transcend terms for people in a manner that engages the realities on the ground.” Dandia recounted how, months ago, minority leader Hakeem Jeffries dismissed Mamdani’s team as “Team Gentrifiers,” drawing a line between natives and transplants. “Zohran said ‘no’ to this,” Dandia continued. “The dividing line is not the accident of birth, but the billionaires who profit and the rest of us.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Mamdani is following a co-governance model, according to Dandia. His transition team involves the “organizations and foot soldiers” of his campaign “to ensure accountability from a more progressive base.” Less than 48 hours after his win, Mamdani posted, “We’re hiring!” with a résumé submission form. Within the first 24 hours, 25,000 people applied to join the civil service. “This is a desire to get involved. This is how to get away from bartering for political positions in backroom deals,” Dandia claimed, pointing to how differently Mayor Eric Adams staffed his administration. Zohran Mamdani, Dandia noted, embodies a politics of affirmation, which, according to him, “Zohran gets from his father.” This stands in contrast to many Democrats, who, in their opposition to President Trump, engage in a politics of endless negation.

While exiting the party, I sloshed around the then-packed crowd until I accidentally collided with Motaz Azaiza, the Palestinian photojournalist who documented a video I will never forget of a boy collecting the flesh of his loved ones in the rubble after Israeli bombardment.

Zohran Mamdani’s victory cannot be separated from the ongoing genocide of Palestinians. In many ways, it is a consequence of it. Bisan Owda, a Palestinian journalist still in Gaza, congratulated New Yorkers on Mamdani’s win, naming it the “Gaza Effect.” As community organizer and nonprofit founder Rana Abdelhamid told me, “Many Muslims experienced heightened Islamophobia over the last couple of years—whether being fired for expressing political views, detained on campuses, or harassed on the street for wearing a hijab. To see a candidate who was committed to Palestine, who called for Netanyahu’s arrest, mattered to Muslim voters.” Brooklyn-based performance artist Isa Hussain further explained, “Protests about Palestine are also for the people to signal to one another what we are thinking. Mamdani was in a successful position because he happened to be a reflection of what people said they wanted.”

When I bumped into Azaiza’s torso, he was smiling softly and filming the celebration. Taken by jubilation, I foolishly asked, “A hopeful night?” to which he replied, “Not really. A hundred thousand people are dead. But this? It’s a start.”

More from The Nation

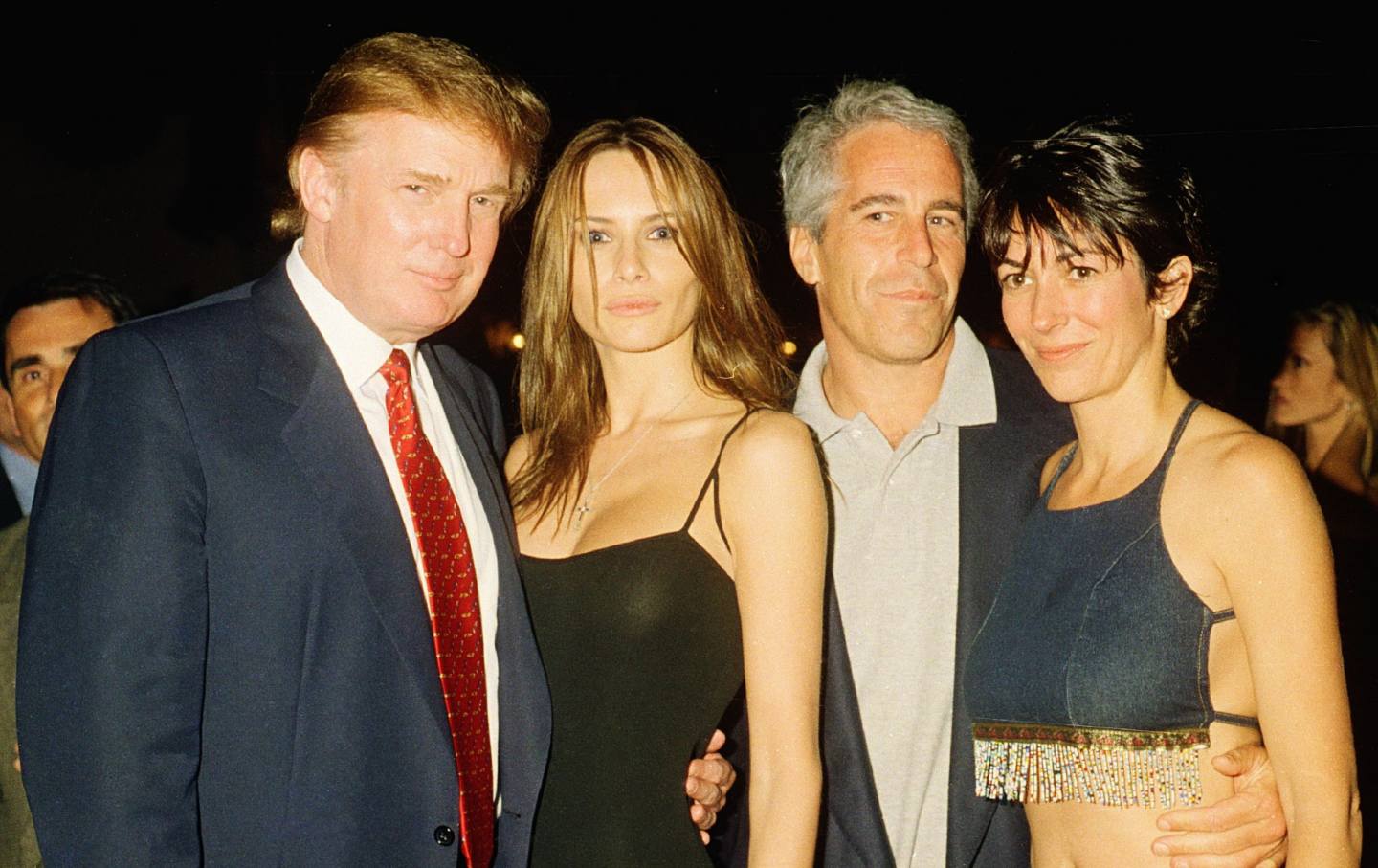

New e-mails show Trump knew of Epstein’s trafficking. As sickening as it is, it should be no surprise.

Dean Fuleihan, Mamdani’s incoming first deputy mayor, speaks exclusively about how the mayor-elect will make his agenda a reality.