November 5, 2025

In the face of Reagan’s right-wing presidency, he offered a vision, strategy, and agenda that would have led Democrats and the country in a very different direction.

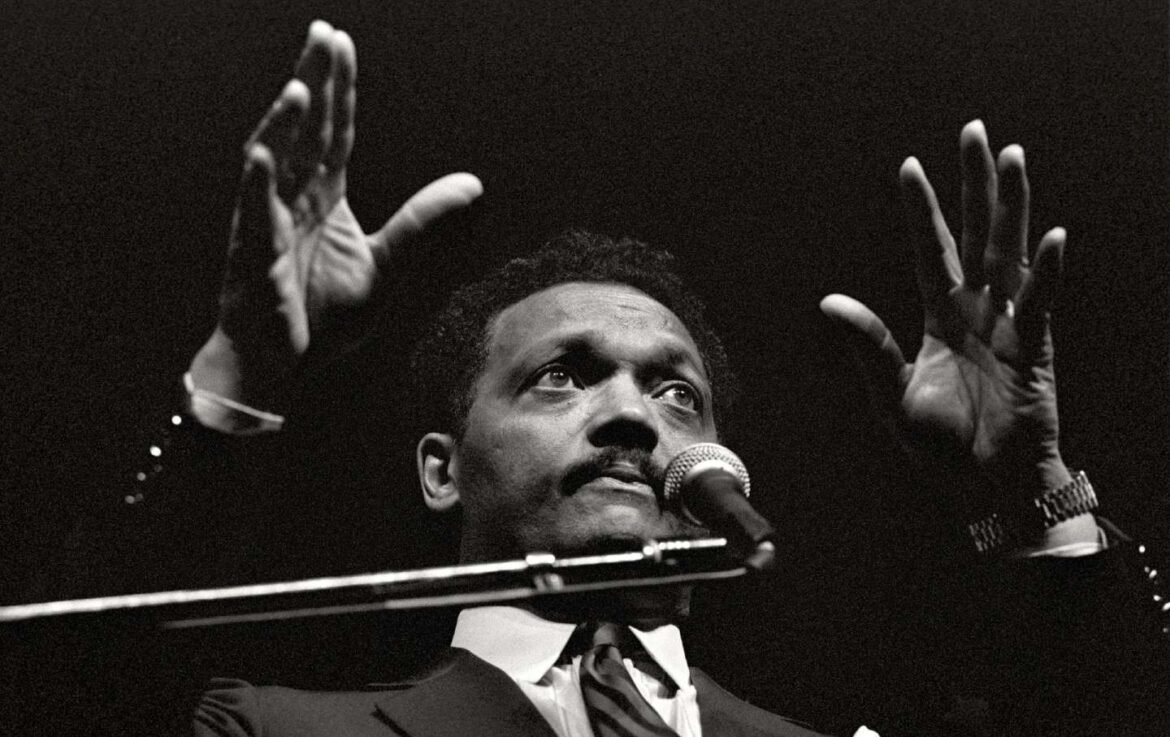

Jesse Jackson is one of the very most significant political leaders in this country in the last 100 years,” Senator Bernie Sanders noted in an event honoring Jackson in 2024.

Now a new book, Jesse Jackson and the Fight for Black Political Power, by Abby Phillip, the Emmy Award–winning CNN anchor, provides a compelling narrative that proves Sanders’s point. Phillip traces Jackson’s remarkable journey up from poverty in Greenville, South Carolina, still ruled by Jim Crow segregation, through working with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in SCLC, creating PUSH—People United to Save Humanity—in Chicago, to his historic 1984 and 1988 presidential campaigns.

Phillip demonstrates how Jackson transformed American politics, registering and rousing millions of African Americans to vote, demonstrating the power of a Voting Rights Act the right-wing majority on the Supreme Court is on the verge of gutting. Jackson’s campaigns helped Democrats take back the Senate in 1986, and kicked down the door for others to follow, including David Dinkins, the first African American Mayor of New York City, Paul Wellstone, the progressive Senator from Minnesota, Carol Mosely Braun, the first African American female senator, and many others. As Phillip documents, Jackson’s reforms of Democratic Party rules “made possible the election of the first Black president,” Barack Obama.

Phillip argues that much of Jackson’s agenda, scorned as radical in the 1980s, is now conventional wisdom. At a time when the United States embraced apartheid South Africa as an ally and tarred Nelson Mandela as a terrorist, Jackson argued correctly that Mandela was a freedom fighter, and the South African government were the terrorists. He called for statehood for Palestinians and welcomed Arab Americans into his coalition a decade before it became common sense.

Philipp suggests that the core of Jackson’s message—economic populism, “warning that corporate interests had left the American worker behind”—represent “ideas that now animate both Democratic and Republican parties.” Would that it were so.

Rather, what is striking about Jackson’s brilliance and most relevant to our politics today is that in the face of Reagan’s right-wing presidency, he offered a vision, strategy and agenda that would have led Democrats and the country in a very different direction. It was, alas, a path not taken, a lesson that speaks directly to our political straits today.

With his victory in 1980, Ronald Reagan became first right-wing movement president in the modern age. He immediately moved to pass massive tax breaks for the rich, double the military budget in peacetime, and fire striking PATCO workers, declaring open season on workers and their unions. Abroad, he launched a new Cold War, a nuclear buildup, wars on Central America. At home, he moved to dismantle social welfare programs, roll back environmental, consumer and workplace protections, celebrate free trade and big oil, even ripping down the solar panels Jimmy Carter had built on the White House roof.

On the defensive, Democrats responded largely by tacking to the prevailing winds, favoring slightly smaller tax cuts, marginally less military spending, somewhat less harsh welfare cuts. The right of the party—galvanized by the DLC (which Jackson immortalized as Democrats for the Leisure Class)—scorned New Deal and Great Society liberalism and argued that Democrats had to distance themselves from “special interests” like unions, the civil rights and pro-choice movement, be more bellicose on national security, more conservative on social welfare, while “reinventing” government to embrace privatization and deregulation.

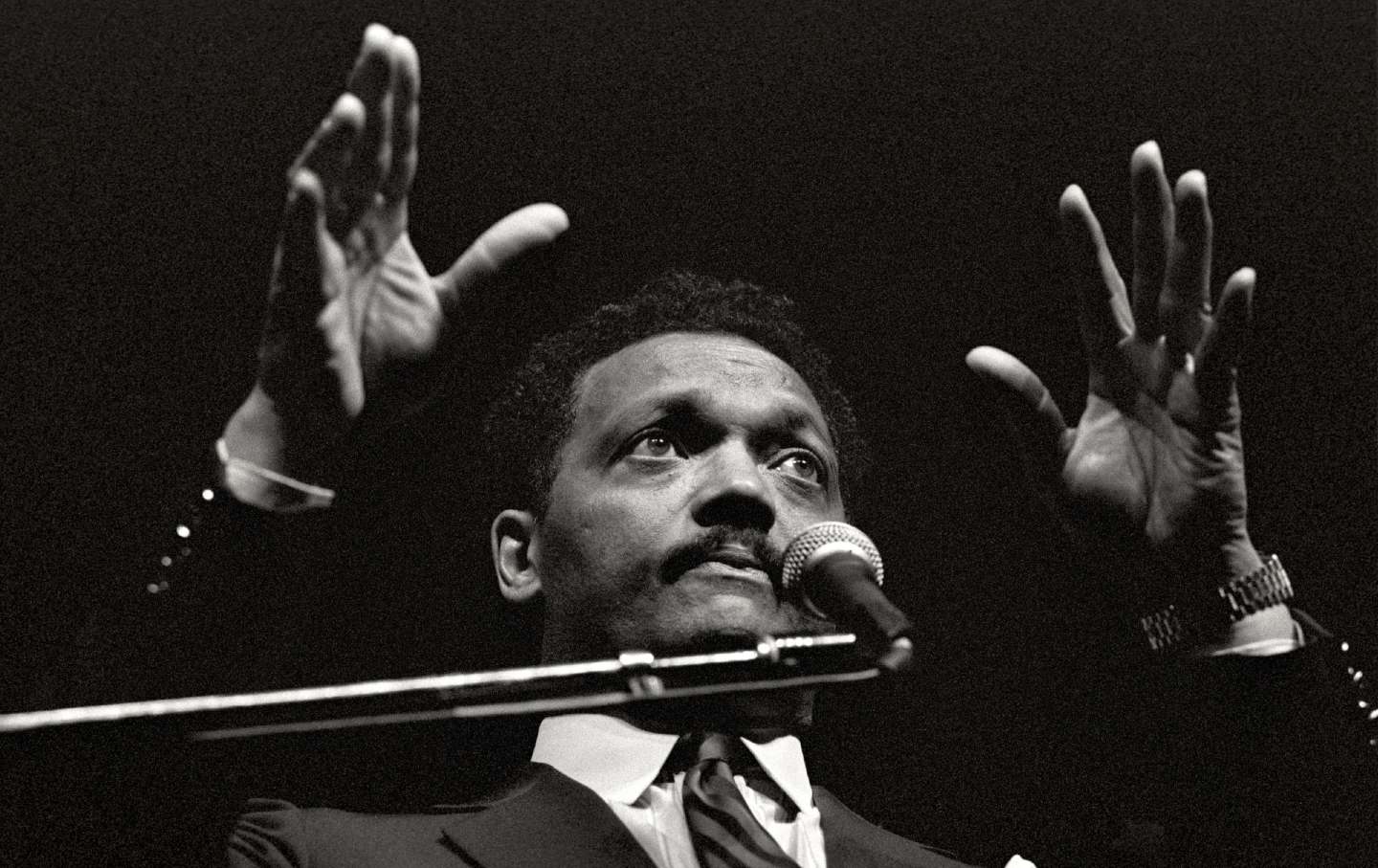

Jackson posed a direct and stirring challenge to both the Reagan reaction and the “New Democrat” pusillanimity. A preacher and not a politician, or as he put it “a tree shaker not a jelly maker,” Jackson was short on the money and the mechanics of presidential campaigns. What he had was a “mission and a message.”

Strategically, he argued that it was time to expand the party, not divide it. His first target was the millions of African Americans who were locked out and left out of electoral politics. In 1984 with most black political leaders committed to the Democratic Party establishment and opposing his candidacy, Jackson stumped across the country and electrified those who heard him speak. His movement registered and mobilized millions—and in 1986, what Alabama Senator Howell Heflin called the “new votahs” led Democrats to take back the Senate, winning seats across the South.

Between 1984 and 1988, Jackson worked tirelessly to expand his coalition. He stood with working people “at the point of challenge,” walking picket lines, joining family farmers resisting foreclosures, marching with peace activists, gays and lesbians, environmentalists.

His goal was to build a progressive rainbow coalition “across ancient boundaries of race, religion, region and sex.” His message focused on the “economic violence” that was ravaging working and poor people. It was time he argued to move “from racial battlegrounds to economic common ground and on to moral higher ground.”

Even as he appealed to shared economic interests, he embraced the specific concerns of progressive movements. He used the metaphor of his grandmother’s quilt. “Workers,” he would argue, you’re right, you deserve a living wage.

“But your patch isn’t big enough. Women, you’re right, you deserve equal pay and comparable worth. But your patch isn’t big enough, etc. We must do what my grandmother did, take scraps of cloth, different patches, different colors, and sew them together with a strong cord to make a quilt, thing of beauty and warmth.”

He put meat on his message, offering a bold strategy for a new direction. Create a national investment bank to rebuild America. Raise taxes on the rich, cut the military budget and double the money going to educate our children. He pushed for empowering workers—raise the minimum wage, make organizing unions easier, equal pay for women, family leave—and holding corporations accountable—a corporate code of conduct, notice and reparations for plant closings. “When the plant closes and the lights go off, we all look the same in the dark.”

He championed a national healthcare plan, what now would be called Medicare for All, and Head Start and daycare, what now would be called the care agenda. And unlike all his opponents, he even put out a budget to prove that we could pay for our dreams.

Rather than retreat in the face of reaction, he urged Democrats to make their case clear, to claim and defend the “moral center.” With Reagan peddling lies about Cadillac-driving “welfare mothers,” Jackson educated people about reality: “Most poor people are not lazy. They are not black. They’re mostly white, female and young. Most poor people are not on welfare. They work every day. They catch the early bus.”

Against the odds, Jackson garnered 7 million votes in 1988, more than Mondale had won in claiming the nomination in 1984. In 54 primary contests, he came in first or second in 46.

But the Democratic establishment wasn’t open to change. In 1984, it chose Jimmy Carter’s former vice president Walter Mondale as its nominee. He made Reagan’s massive deficits a focus of his campaign, promising to raise “your taxes.” In 1988, the nominee, Massachusetts’s Governor Mike Dukakis, campaigned on “competence,” and chose a Texas Senator, Lloyd Bentsen, a bourbon conservative as his running mate. Neither offered a clear choice; neither had a chance.

In contrast, in 1992, Bill Clinton won by embracing Jackson’s populism, championing a national healthcare plan, taxes on the rich to invest in rebuilding the country, opposition to NAFTA—while combining it with sly racial posturing: promising an end to “welfare as we know it” and harsher criminal penalties, and blindsiding Jackson with his infamous Sister Souljah cheap shot. Sadly, once in office, he turned the economy over to Goldman Sach’s Bob Rubin and governed, as he put it, like “Eisenhower,” only without the roads.

Barack Obama embraced Jackson’s rhetoric of hope and of unity, and won the nomination largely fueled by the backing of movement energy against the party establishment. He won reelection by adopting an even more populist rhetoric, in the wake of Occupy, against the hapless candidate of the 1 percent, Mitt Romney. But again, his economic policy was guided by Wall Street, bailing out the banks in the wake of the financial collapse, while abandoning victimized homeowners, and turning to austerity even with unemployment over 10 percent.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Today, Democrats face another right-wing movement president, this time peddling a right-wing populism—railing against the failed elite, promising America First anti-interventionism, and an economic strategy combining protectionism and anti-immigration with old conservative staples like top-end tax cuts, deregulation, and race-baiting politics.

Once more, Democrats trumpet the sound of caution. Simply stand for repeal, argues a shopworn James Carville, promising only a return to what has failed in the past. Embrace deregulation and reinventing government, argues the newly fashionable “Abundance” crowd, treating the challenge as one of competence rather than one of direction. Tack to the right, recycles the well-financed, renamed New Democrats—curb social liberalism, get more muscular on the military and national security, forget about big reforms like Medicare for All.

Once more, the Jackson campaigns—and Bernie Sander’s campaigns more recently—offer a different and necessary alternative: Build a coalition grounded on economic common ground; stand up, don’t retreat; educate, don’t apologize; expand and excite the activist base of the party, rather than divide and demoralize it. Put forth a big strategic agenda that addresses the real needs of working people.

This is the path not taken in 1984 and 1988. It is the path not taken in the wake of Trump’s first administration. The path not taken in the face of his reelection drive. The money, the entrenched interests, the establishment are all intent on recycling the failures of the past. It will take an insurgency—like that fueled by Jackson in the 1980s or Sanders more recently—to provide Americans with a choice and a chance. Jackson’s campaigns were four decades ago, but, as Abby Phillip reminds us, his message, his strategy, and his agenda remain a beacon for a new direction.

More from The Nation

Democrats stormed back to dominance, winning all three statewide races and a stunning 13 seats in the House of Delegates.