From the Cold War till Donald Trump, there’s always been a special dispensation for hawkish bigots.

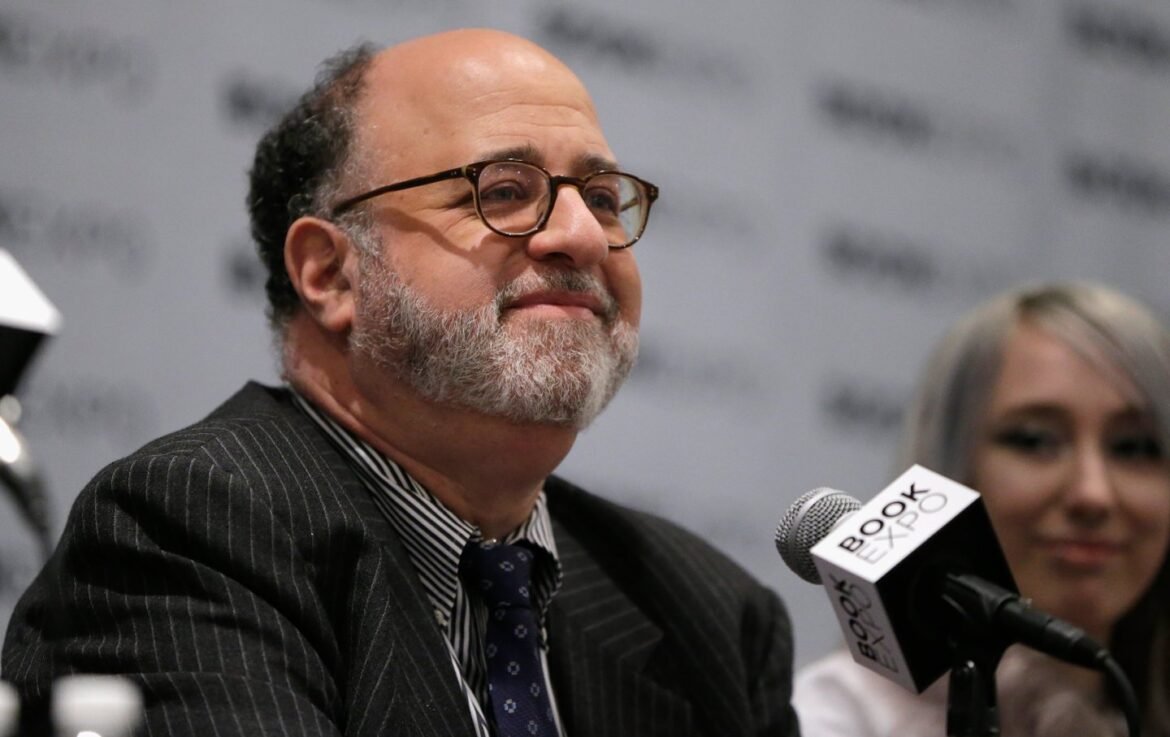

John Podhoretz inherited from his famous parents his neoconservative worldview, an editorial sinecure at Commentary magazine, and the charming habit of presenting his ideas in so crude and blunt a fashion as to be self-discrediting. Podhoretz is the son of the late Midge Decter (who started working for Commentary in 1950) and Norman Podhoretz (who edited Commentary from 1960 to 1995 and remains on the masthead as editor at large). Commentary was founded in 1945 by the American Jewish Committee (AJC), so for the vast majority of its history it has been under the sway of one Podhoretz or another. Aside from the trio just named, the magazine has also published Naomi Munson (Midge and Norman’s daughter), Rachel Abrams (another daughter), Steven C. Munson (a son-in-law), Elliot Abrams (another son-in-law), and Sam Munson (a grandson). Not surprisingly, in 2003 Commentary published an excerpt of the book In Praise of Nepotism, by Adam Bellow (son of the famous novelist, who was also a Commentary contributor).

In launching Commentary, the AJC outlined a mandate that included aiding “in the struggle against bigotry.” It’s perhaps just as well that Commentary severed its relationship with the AJC in 2007, since today Commentary can more accurately be called a magazine devoted to aiding and abetting bigotry—including even at times anti-Jewish bigotry. The magazine has been animated with an obsessive anti-Black animus dating back to the 1963 publication of Norman Podhoretz’s notorious essay “My Negro Problem—And Ours.” Decter’s equally infamous 1980 essay “The Boys on the Beach” was a spectacular airing of hatred for gays and lesbians.

Now the Podhoretz scion has made his own contribution to this tradition. At a rally on July 3, Donald Trump praised the recent budget his party passed in these terms: “Think of that: No death tax. No estate tax. No going to the banks and borrowing from, in some cases, a fine banker—and in some cases, Shylocks and bad people.” This casual use of the term “Shylocks” was a relatively venial sin compared to Trump’s many other bigoted words and deeds (ranging from his 2017 “very fine people on both sides” comment in response to a neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, to the current immigration crackdown), but it was still noxious and rightly condemned as antisemitic.

John Podhoretz had a different view. On the social media site X, Podhoretz tweeted, “Trump bombed Iran. He can say Shylock 100 times a day forever as far as I’m concerned.” With an admirably succinct brutality, Podhoretz articulated a long-held neoconservative principle: that bigotry, even antisemitism, is forgivable if done by someone who supports American militarism.

This history of this idea is worth tracing. Because Podhoretz is a Zionist and because the Iran bombing was conducted at the behest of Israel’s prime minister, it might be thought that the special license to antisemites is a narrow matter of supporting the Jewish state. In fact, there has long been a wider support of military hawkishness at play.

Before Commentary made its neoconservative turn in 1970, it was an organ of Cold War liberalism. The neoconservative attachment to Israel was combined with an older and deeper attachment to American empire. Within the context of the Cold War, it was often necessary to refurbish the reputation of various far-right (in some cases fascistic) figures who were stalwart anti-communists. This was expressed in the apocryphal adage attributed to Franklin Delano Roosevelt about a Latin American dictator: “He may be a son of a bitch, but he is our son of a bitch.”

In the context of Cold War, allying with “our SOBs” often meant working with antisemites and even “former” Nazis (as in the CIA’s recruitment of war criminals in Operation Paperclip). Intellectuals played a role in this Cold War laundering of the far right. In 1960, the historian Gertrude Himmelfarb (later a neoconservative doyen and Commentary contributor) published an essay celebrating the British novelist John Buchan in Encounter (a Cold War liberal magazine covertly funded by the CIA and edited by her husband, Irving Kristol, another Commentary contributor). Buchan was an odd figure for Himmelfarb to enthuse over. Best known as the author of The Thirty-Nine Steps, Buchan was mostly a mediocre Rudyard Kipling knock-off—a writer of boy’s adventure books celebrating empire and chaste athleticism.

Buchan’s spy novels also had a distinctly antisemitic agenda, featuring Jewish financiers who plotted the destruction of Western civilization. Himmelfarb characterizes these stories as “Jewish-capitalist-communist conspiracies.” This narrative is a pulpy expression of the myth of Judeo-Bolshevism—the claim that Jews are covertly behind both capitalist and communist machinations, which formed a crucial ideological rationale for the Holocaust.

In her essay, Himmelfarb goes out of her way to exonerate Buchan, claiming that his bigotry was “the innocent antisemitism of the clubman.” She also notes that Buchan was a Zionist. Himmelfarb argued:

This is not to suggest that Buchan’s novels can be acquitted of the charge of anti-Semitism. They were anti-Semitic in the same sense that they were anti-Negro. If the Jews, unlike the Negroes, were not in all ways inferior, they were most certainly different…. But this kind of anti-Semitism, indulged in at that time and place, was both too common and too passive to be scandalous. Men were normally anti-Semitic, unless by some quirk of temperament or ideology they happened to be philo-Semitic. So long as the world itself was normal, this was of no great consequence. It was only later, when social impediments became fatal disabilities, when antisemitism ceased to be the prerogative of English gentlemen and became the business of politicians and demagogues, that sensitive men were shamed into silence. It was Hitler, attaching such abnormal significance to filiation and physiognomy, who put an end to the casual, innocent anti-Semitism of the clubman. When the conspiracies of the English adventure tale became the realities of German politics, Buchan and others had the grace to realize that what was permissible under civilized conditions was not permissible with civilization in extremis.

On the face of it, this defense is nonsense. Writing novels in the 1920s featuring “Jewish-capitalist-communist conspiracies” goes well beyond casual social disdain. It is a profoundly ideological act that clearly echoes conspiratorial and exterminationist antisemitism—the proof can be seen in the fact that Buchan stopped writing in this fashion after the rise of Hitler in the 1930s alarmed him. Himmelfarb also waves away Buchan’s anti-Black racism (seen in his frequent recourse to the n-word) by saying it displayed “the virtue of candor” lacking in liberals who use more evasive language in talking about the race problem.

In his 1988 book T.S. Eliot and Prejudice, the literary critic Christopher Ricks argues that Himmelfarb’s need “to reinstate John Buchan as politically exemplary in some ways and certainly as an ally against certain kinds of misguided sensitivity” led her to come up “with an amnesty not only for him personally but for a whole world of suavely brutal bigotry.” Ricks suggests that Himmelfarb was motivated to do so by anticommunism.

The same granting of a special exemption to antisemites if they were sufficiently anti-Communist can be seen in the way neoconservatives defended the Argentine Junta during the Dirty War of the 1970s and ’80s. During this ferocious counterinsurgency, tens of thousands were tortured and killed. In 1981, Jacobo Timerman, who had been tortured for two and half years by the Argentine regime, wrote about the experience in his memoir Prisoner Without a Name, Cell Without a Number. The book makes clear the antisemitic nature of the regime: The prison walls were plastered with posters of Adolf Hitler, and Timerman was taunted by his torturers shouting, “Jew! Jew! Jew!” Guards painted swastikas on the backs of Jewish prisoners.

Writing in The Wall Street Journal, Irving Kristol launched a fierce attack on Timerman for his “irresponsible and dishonest demagoguery.” According to Kristol, the Argentine regime was “doing…its best” to fight antisemitism. A 1981 article by Mark Falcoff in Commentary took the same tack of questioning Timerman’s reliability as a memoirist and minimizing the viciousness of the Argentine regime.

Kristol’s argument was both factually absurd and morally obscene. As Haaretz reported in 2018: “By the early 1980s, possibly up to 30,000 political opponents had been rounded up and never heard from again (the ‘disappeared.’) A disproportionate 10 per cent of these victims were Jews.”

In 1999 a controversy over the antisemitism of the TV evangelist Pat Robertson, a leader of the religious right, erupted. Writing in Commentary, Norman Podhoretz noted that Robertson had written a book promoting “a crackpot theory according to which bankers like the Rothschilds, Paul Warburg, and Jacob Schiff were major players in a centuries-old but still active conspiracy to take over the world.” Because Robertson also saw Jewish groups as subverting traditional norms, his ideological concoction can fairly be described as a modernized version of the myth of Judeo-Bolshevism. As Podhoretz acknowledged, “The conclusion is thus inescapable that Robertson, whether knowingly or unknowingly, has subscribed to and purveyed ideas that have an old and well-established anti-Semitic pedigree.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Having said that, Podhoretz minimized this antisemitism as irrelevant because Robertson “has also been one of the staunchest defenders of Israel in America.” Podhoretz admitted that Robertson’s pro-Israel politics were an outgrowth of an apocalyptical theology that requires a Jewish state to be the final site of Armageddon, leading to mass Jewish conversion (among the survivors of this catastrophe) to Christianity.

Podhoretz waives this problem aside as irrelevant to real world politics:

Since Robertson’s support of Israel is undeniable, the usual tactic of those who wish to convict him of anti-Semitism is to denigrate that support by explaining that in his apocalyptic theology, the return of the Jews to the Promised Land is a necessary prelude to the second coming of Jesus and their ultimate conversion to Christianity. But surely in politics it is actions and not motives that count. And in any event, since Jews do not share Robertson’s belief in Jesus, why should they worry about what he thinks will happen after the second coming, in which they also do not believe?

What Podhoretz doesn’t acknowledge is that Christian apocalyptic theology is not a problem for him because he himself is a militarist who believes Israel must be a Sparta at eternal war with its neighbors (and eternally oppressive towards the helot peoples who live under its domination). Apocalyptic Christians are urging militarism for their own end-times reasons and so Podhoretz can work with them.

But for anyone who believes that Israel should pursue a path of negotiations and not war—let along justice toward the Palestinians—Robertson’s theology is far from being a reason to ignore his antisemitism. Whether Podhoretz is worried or not, pushing Israel to be ground zero for the next world war—one that will end with the extinction of Jews as a separate people—is itself a lurid and demented form of antisemitism.

In our time, neoconservatism is fragmenting, and one faction is vocally anti-Trump. William Kristol, the son of Gertrude Himmelfarb and Irving Kristol, seems to have moved on from some parts of his parent’s legacy. Although he supports bombing Iran, the younger Kristol has even denounced Trump’s “Shylock” comment. This is a small step in the right direction. But honesty also requires noting that John Podhoretz much more accurately represents the toxic legacy not just of neoconservatism but of the wider project of American militarism.