As the Trump administration escalates its campaign to reshape education, a provision in the “Big Beautiful Bill” will raise the tax on select private colleges’ endowments.

Donald Trump pauses in the Cross Hall to listen to the band at the conclusion of the “One, Big, Beautiful” event

at the White House.(Chip Somodevilla / Getty)

When President Trump first signed a bill in 2017 eliminating the tax-exempt status enjoyed by many private university endowments, Representative Kevin Brady—the key congressional Republican overseeing the tax code rewrite as chairman of the powerful Ways and Means Committee—said the goal of the new tax was “pretty simple: It encourages colleges to use their major endowments to lower the cost of education.”

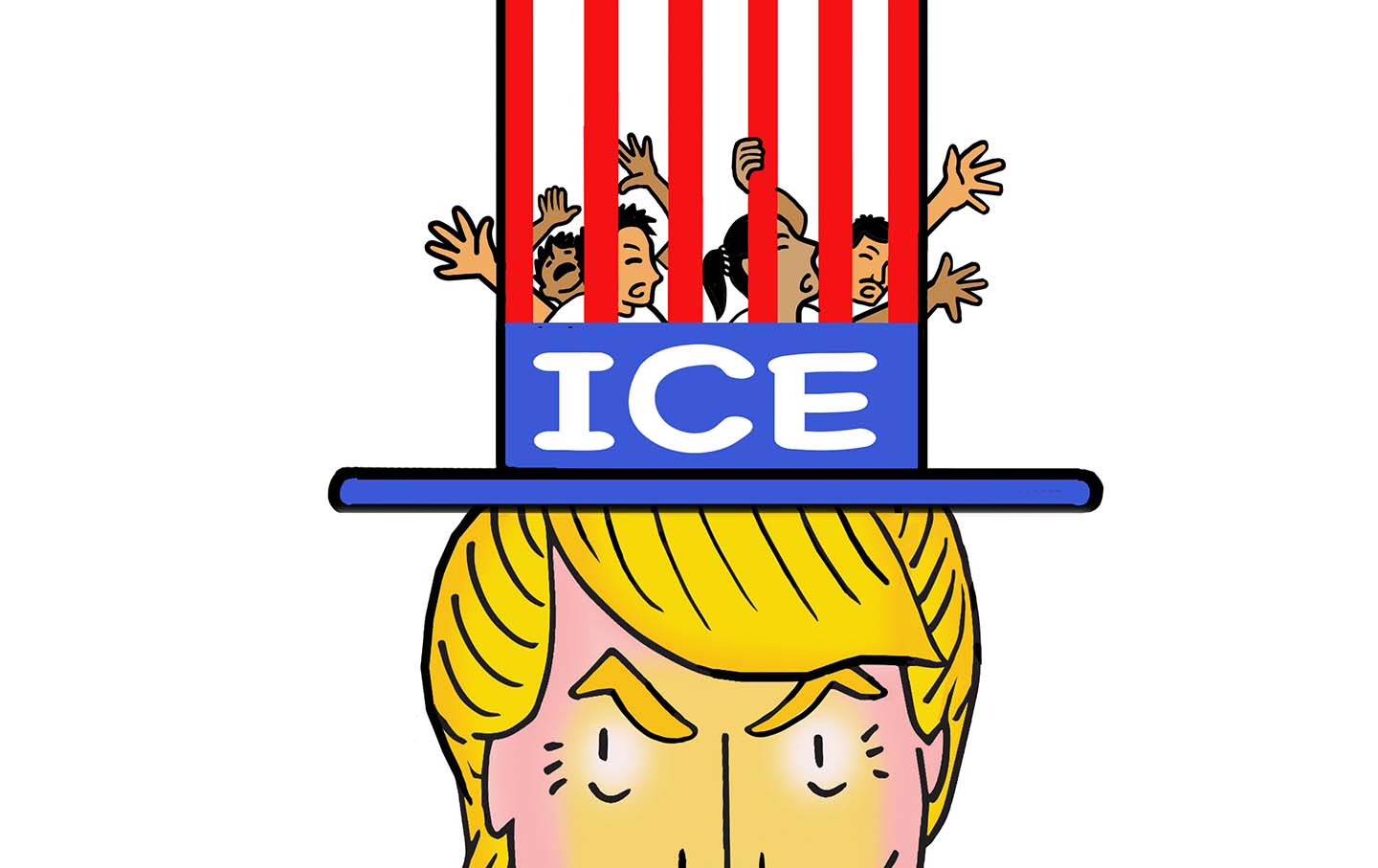

In the face of a further tax increase on a small subset of private colleges in the United States, the GOP’s rationale has shifted. Brady’s successor, Representative Jason Smith, has pitched the increased levies as a way to hold “elite, woke universities and nonprofits accountable.”

Tucked inside Republicans’ 800-plus page “One Big Beautiful Bill” is a provision raising the tax on earnings from select private college endowments from its current 1.4 percent rate to anywhere from 4 to 8 percent. The levy is calculated by dividing the size of the school’s endowment by the number of non-international students they enroll, outputting a figure representing the amount of money held in the endowment per student. The higher the per-pupil endowment rate, the higher the tax. This creates an incentive structure, Republicans argue, that encourages colleges to spend more of its endowment on financial aid and the students’ learning experience, rather than hoarding its wealth into what are effectively hedge funds. But higher education experts dispute this, asserting that endowments serve to lower the cost of the education.

In a survey of 645 US institutions by the National Association of College and University Business Officers, financial aid accounted for nearly half of all endowment spending. Academic programs and research accounted for another 17 percent and faculty positions for nearly 11 percent. “Faculty and staff certainly benefit from this philanthropy, but students remain the primary beneficiaries, as the bulk of these resources is used to maintain student aid and affordability,” NACUBO president and CEO Kara Freeman said.

Increasing the tax burden for these colleges could divert funds from these programs, negatively impacting access to education, Phillip Levine, a senior nonresident fellow at the Brookings Institution and an economics professor at Wellesley College, told The Nation. “These highly endowed colleges are the least expensive college options for students below perhaps $150,000 in income per year,” he said. “They are able to do that because of their large endowments.”

Another GOP qualm, as Smith puts it, is that colleges have used their multibillion-dollar slush funds to push political ideology. “That ends now. If these institutions want to act like corporations, we’ll treat them like corporations.”

Endowments, however, have strict rules governing them. The amount of money that can be pulled from them annually is regulated by state laws. Donors also stipulate how their money can be used. Some donate to endow professorships. Others donate to increase student financial aid, fund construction of a building, or fund research.

Existing in a largely tax-exempt world since the early 1900s, higher education institutions have enjoyed a federal tax carveout due to their mission and contribution to civil society. “Higher education absolutely has a civic responsibility,” James Murphy, the director of postsecondary policy at Education Reform Now, said in an interview, citing its ability to provide social mobility to students and advance scientific inquiry.

Steven Bloom, the assistant vice president of government relations at the American Council on Education, went as far as to call US higher education “a national security asset.” “They are a magnet for the world’s brightest students and scholars,” he said of the nation’s colleges and universities.

In a 2019 paper, Mae C. Quinn, a law professor at Penn State, argued that colleges could simply use their endowment in ways that make higher education more equitable, such as on financial aid. Spending down these endowments would exempt them from a tax while simultaneously benefiting disadvantaged groups who are under threat from the Trump administration, she wrote during Trump’s first term. “If rich colleges simply utilize more of their massive savings to further social justice, impact poverty, and enhance public good—particularly in their own at-risk communities—they will not only avoid federal taxation but also begin to address critiques about their elitism and greed,” Quinn wrote.

But as the Trump administration escalates its campaign to reshape US postsecondary education by withholding billions in federal funds and launching countless investigations, this latest tax is seen as punitive by education stakeholders across the political spectrum.

“The tax is explicitly directed at ‘woke’ universities,” said Neal McCluskey, the director of Center for Educational Freedom at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank. “The tax system should not be used to punish people for their ideological beliefs.” But McCluskey does think that the federal government should cut off all funding to higher education, “not to punish higher education but to follow the Constitution, which gives Washington neither the authority to fund student aid nor most research.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Hillsdale College follows this model. A conservative-leaning religious institution, Hillsdale has refused any federal funding since its founding in 1844, pointing out that government funds can come with strings attached. Yet its president, Larry Arnn, has publicly rebuked the endowment tax, arguing that “it penalizes most severely those institutions that have chosen the harder path of independence, that refuse the entanglements of federal subsidy.”

Much of the school’s funding comes from philanthropic gifts. “To tax these gifts is to tax philanthropy itself—to burden those who would lift burdens,” Arnn wrote. If the tax were to go into effect, “it would force us to cut resources, to limit opportunities, to pass burdens onto students and their families—all in the name of a fairness that is not fair.”

Other colleges have expressed similar alarm, predicting doomsday scenarios if Trump enacted such a levy. On Friday, Trump signed the legislation, and the new tax, into law. The Nation reached out to dozens of colleges to understand how they are preparing for the tax hike and how it would affect their students. Only one, Baylor College of Medicine, provided a response, saying it didn’t believe that the tax was meant to target small, private medical schools. “We are currently working with our elected representatives to effect a solution to this issue,” added Robert Corrigan, BCM’s general counsel.

These institutions have lobbied extensively on Capitol Hill against such proposals to raise the tax, according to public disclosure documents reviewed by The Nation. Bloom lobbies about these taxation issues on behalf of the American Council on Education, an organization of 1,600 higher education institutions. His pitch against the tax evokes traditional Republican themes of a small federal government. By taxing these earnings, he argues to lawmakers, “you take the money away from other useful purposes and send it to Washington.”

Some in higher education are still fighting against the endowment tax, but are open to reforms. Murphy has proposed leveraging the punitive measure of a tax to spur colleges into working toward “desirable outcomes.” In his view, this would include tax breaks for those that eliminate legacy preferences in admissions or surpass a threshold in the percentage of students enrolled who are Pell Grant–eligible. Bloom said that ACE wants the tax repealed or “reformed in ways that enhance or incentivize schools to do more in terms of financial aid and research.”