June 24, 2025

A new documentary about the 1975 fiscal crisis, Drop Dead City, is entertaining to watch but dangerously misleading as history—or politics.

Drop Dead City, a documentary about the 1975 New York fiscal crisis, is well-timed for this budget-cutting age of Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill and Elon Musk’s chain saw, though less as critique than as exculpating history. The resolution of that crisis—deep cuts in public spending and services—was the opening act in a global five-decade austerity campaign that has yet to end. This film, though rich in interviews with principals, from a colorful sanitation union guy to a fiscal watchdog who says “fuck” a lot, and replete with evocative visuals from the 1970s—an era of comical fashions and prominent sideburns—nonetheless comes up way short on the politics. You learn very little about the class war in which the fiscal crisis represented a crucial engagement.

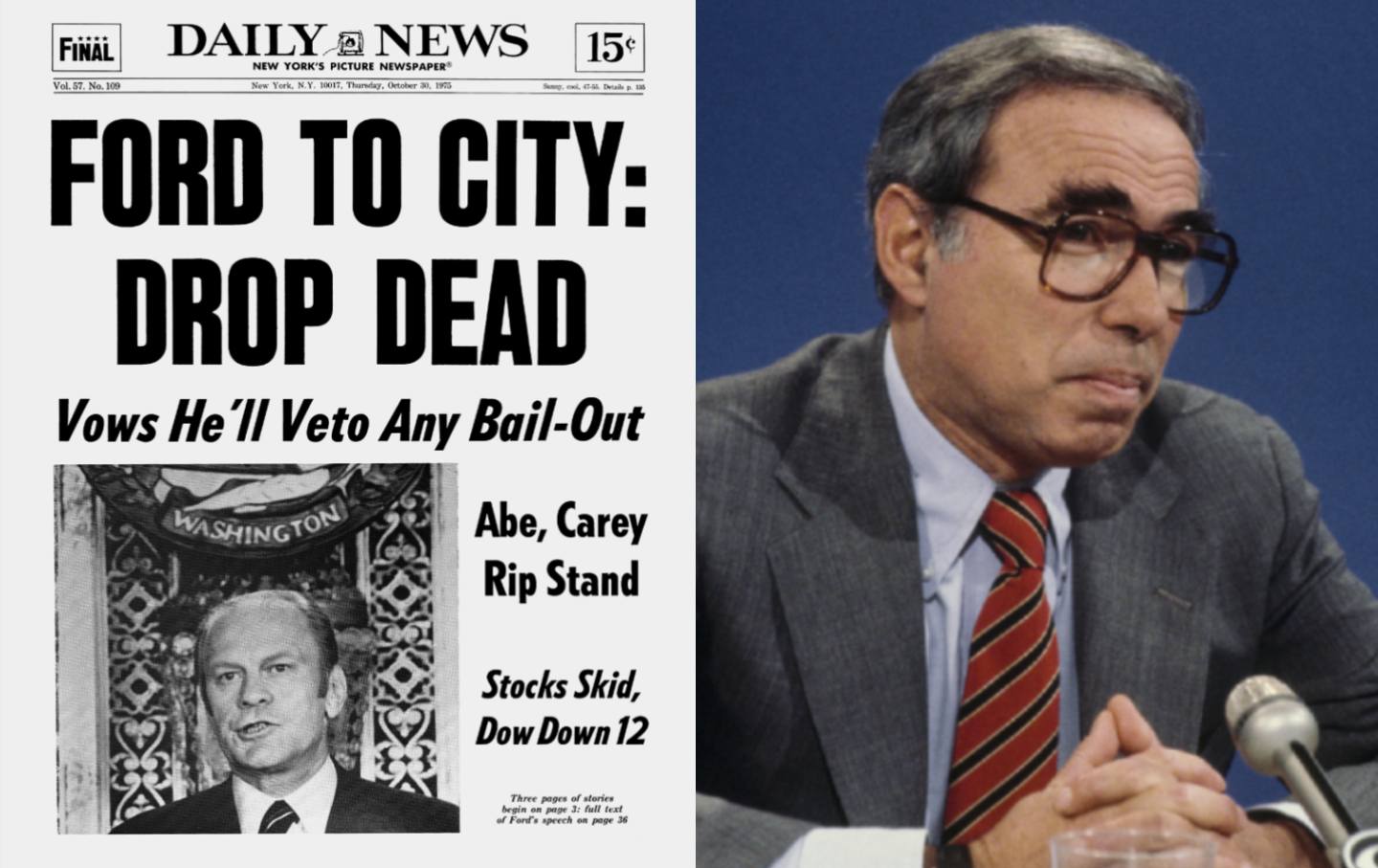

A possible reason for this shortcoming might be that one of the film’s two producer-directors is Michael Rohatyn, son of Felix, top commander of the forces of austerity who is often canonized as the city’s “savior.” Given his prominent role in the crisis, Felix gets a rather modest amount of screen time (though plenty of praise from the supporting cast). It’s surprising he didn’t get more. He doesn’t appear until nearly an hour in. Michael told The New York Times, “I was very moved to see his charm and his intellect right there on the surface. I think he would be really proud of the film. He might think there’s not enough of him in it, and he might be right.” Filial pride can be an admirable thing, but a documentary is the wrong place for it.

The standard story is that during the fat decades of New York’s post–World War II Golden Age, the city got used to spending profligately to fund generous social programs and high wages for unionized municipal workers—without paying much attention to where the money was coming from. For New York, the New Deal never ended. That fiscal insouciance got a boost from a man who personally never had to worry about where the money was coming from: Nelson Rockefeller, who was the state’s governor from 1959 to 1973. Rocky, an old-style liberal Republican, loved spending money, especially on big projects, and was a generous patron to the city.

When the economy turned sour in the 1970s, the city continued to spend, covering its expanding revenue shortfalls by borrowing vast amounts of money. Revenues were weakening because of the disappearance of hundreds of thousands of jobs, many of them in manufacturing. (Hard as it is to believe today, New York was once a major manufacturing center.) Those jobs were disappearing at the same time affluent whites were moving to the suburbs, replaced by poor, dark-skinned people who needed more social services than those they were replacing. Big-name firms moved their corporate headquarters out of the city to the suburbs, a further hit to revenue (and prestige). Worse, the city didn’t know how much it was spending and how little it was taking in because its accounting was a mess. Or, as that sharp-tongued fiscal watchdog, Stephen Berger, put it, “There were no fucking books.”

That canonical story isn’t all wrong. Revenues were collapsing, jobs were disappearing, and only energetic borrowing sustained high spending. New York, with an extensive municipal hospital system and a university that charged no tuition, was trying to run a regime of social democracy in one city that had become unaffordable without major structural transformations. And the books really were a mess.

But there are also some problems with the standard story.

One is that for every borrower who gets in trouble there’s a lender who should have known better. The bankers didn’t start asking serious questions about New York’s rickety finances for years—they were making too much money selling the city’s bonds. Whether it’s the New York City debt crisis, or the Latin American debt crisis that came shortly afterward, or the European debt crisis that broke out in 2008, there have always been sermons about the responsibility of the debtor. The irresponsibility of the creditor is rarely mentioned—and, not coincidentally, the debtor ends up paying most of the costs.

And then there’s the disappearance of factory jobs. Clearly, deindustrialization is a global story, but New York’s planning elite—big real estate in conjunction with city government planning agencies and affiliated nonprofits—made sure it started early and happened big and fast. As Robert Fitch showed in his book The Assassination of New York, and his masterful essay “Planning New York,” those planners wanted the smelly factories and their disreputable workers shipped out to Jersey and replaced by skyscrapers inhabited by more respectable sorts like lawyers and bankers. That would raise rents and property values, which is the leading passion of the real estate sector. What is often presented as a force of nature, the outward movement of manufacturing, had a heavy planning hand behind it. Also, Fitch argued, much of the lamented spending went to projects that real estate interests favored, though of course lurid tales about welfare mothers achieved much wider circulation than that detail. None of this history is in Drop Dead City.

There were signs of trouble for New York City years before it went into crisis. A big chunk of the West Side Highway fell down in December 1973, and a few months later Con Edison skipped a dividend for the first time since it started paying them in 1885—a sign of the city’s failing health. Despite these spasms, the banks kept underwriting the city’s bonds and distributing them—until they had a sudden change of heart in early 1975.

One of the city’s favorite fiscal gimmicks was issuing bonds called “tax anticipation notes.” They sound like something you’d issue to get over a temporary dry patch, but they weren’t. As John Osnato, then a young lawyer for one of the banks, recounts in the movie: “I met with the assistant controller and I asked him a question which he said no one had ever asked before and I said, you are issuing tax anticipation notes. What taxes do you anticipate receiving? And he actually wrote out some information for me on a yellow legal pad and I looked at it and I said, goodness, I don’t think they have the room to back this issuance because if you don’t anticipate receiving taxes because you’ve collected them already, you can’t issue a tax anticipation note. Well, pretty quickly the show kind of collapsed.” The banks—who had never asked this simple question before, though they should have—cut the city off, and panic ensued. When you’re as deep in debt as New York was, you need new loans just to pay off the old ones—and then new loans on top of that to pay your expenses. Could the city pay its debts, or would it have to default and file for bankruptcy?

At first the state, under Governor Hugh Carey, mobilized to deal with the crisis. Carey put together the Municipal Assistance Corporation (MAC, aka Big MAC), led by Rohatyn. The idea was that MAC would assume some of the city’s debt until things could be worked out. Rohatyn was an investment banker at Lazard Frères famous for big mergers, a protégé of Andre Meyer, one of the pioneers of modern financial engineering. From then on, the reconstruction of New York became a project run by bankers, both through the bond market and direct political influence. The elected government of New York City was completely subordinated to finance capital.

Things had already been shifting in the political realm even before the brush with bankruptcy. Carey came into office in January 1975, months before the city’s fiscal crisis really hit, proclaiming “the days of wine and roses are over…we must all live by a rule of austerity for as far ahead as we can see.” The national environment was shifting too. The 1973–75 recession was the deepest since the Great Depression, and it inspired fears that the great postwar prosperity machine had blown a gasket.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

It soon became clear that MAC couldn’t solve the city’s problems. Despite some layoffs and cuts in services—modest by the standards of what was to come—no one wanted to buy its bonds. Without those bond proceeds, MAC couldn’t take up the city’s debt. Avoiding default would require federal intervention.

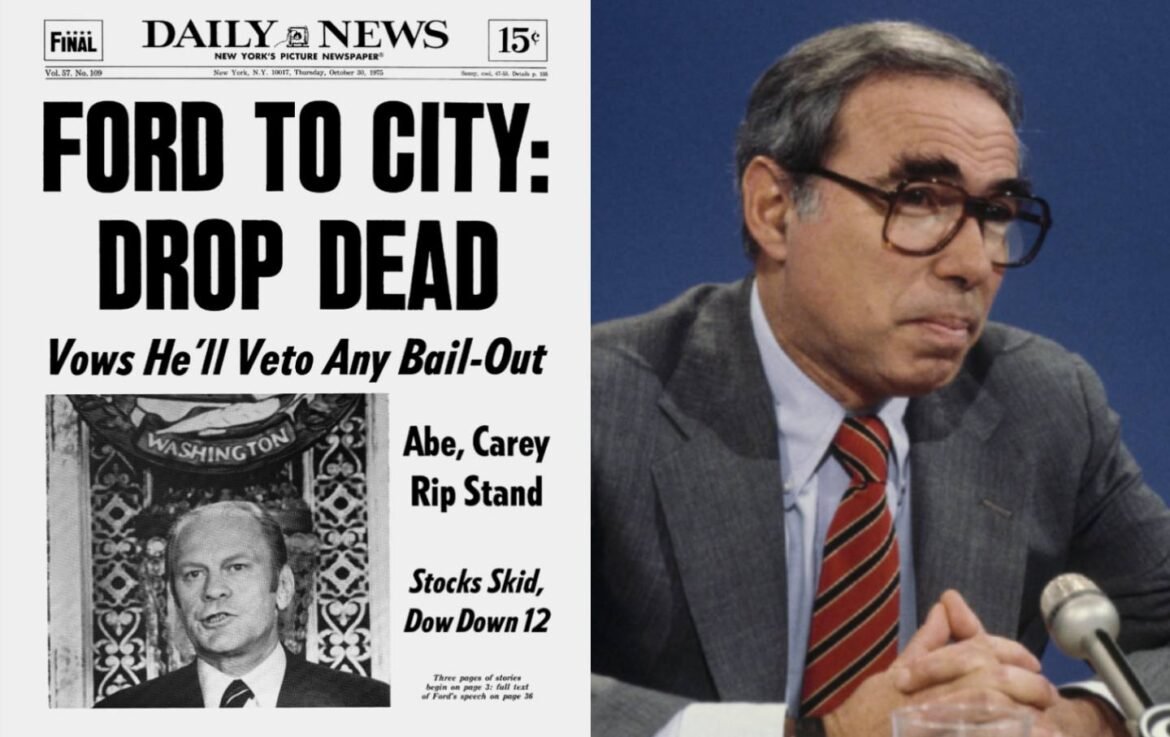

Influenced by advisers Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld, the Ford administration was not enthusiastic. Generous, polyglot New York City was a symbol of everything heartland conservatives hated. In October 1975, Ford said no in the sharpest terms, prompting the Daily News’ classic headline, “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD.”

Despite the tough talk, Ford couldn’t sustain that intransigence. A month later, as historian Kevin Baker recounts in the film, at the first G7 summit in Rambouillet, France, German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt told Ford that the dollar would be “Scheiße,” shit, if New York City defaulted. The Federal Reserve reported that many banks around the country could take serious hits if the city stopped servicing its debt. Fearful of a global financial crisis, Washington finally came through with enough short-term credit to prevent default. The moment of crisis passed, but the local austerity program was only beginning.

And the consciousness it produced is still with us. As journalist Ross Barkan pointed out on X, commenting on the mainstream alarm provoked by the social democratic mayoral campaign of Zohran Mamdani:

The rage at Zohran’s redistributionist arguments is a good example of how thoroughly the post-1970s neoliberal paradigm still dominates NYC. Before 1970, free or cheap public goods were the norm. Free CUNY, massive amounts of public and subsidized housing, cheap transit.

Today any idea that we deserve these things—not just New Yorkers, but everyone—seems as quaint as polyester shirts and two-inch sideburns. Bernie Sanders tried to revive some of that spirit in his presidential campaigns, but it was buried by his own party, including some of its marquee liberal names. As one of those names, the late Representative John Lewis, said in 2016, batting down Bernie: “There’s not anything free in America…. I think it’s very misleading to say to the American people, we’re going to give you something free.” Lewis was one of the organizers of the 1963 March on Washington, whose agenda included an ambitious economic program. Rohatyn was a pioneer in making it acceptable for liberal Democrats to say things like that.

Drop Dead City puts a lot of emphasis on the shifting national scene. Ford’s Treasury Secretary, William Simon, was a right-wing financier who wanted to put the city through a wringer, and with it, a whole model of governance. There’s a clip of Simon saying before Congress, “We have to determine whether the priorities, practices and procedures of the past in all areas, welfare, housing, all assistance programs such as rent control.” (The statement is missing a conclusion in the original; presumably Simon meant something like “can be sustained.”) Politically, Ford was nervous about the threat on his right coming from Ronald Reagan—also no friend of the city.

But the movie underplays the contribution of liberals to the construction of the austerity regime, starting with Rohatyn himself (as well as Carey, who appointed him, and many of his advisers). There’s a scene where Felix professes concern about the human costs of default should things come to that: “The social dislocation caused by a default, the hardships to the people of the city, the possible cut in services. It certainly seems to be a risk that is so large that every effort should be made to avoid it.”

As head of MAC, Felix would go on to engineer such dislocation himself, through mass layoffs and deep cuts in public services. He had a lot to do with the imposition of tuition at the City University of New York, which had been free since its founding in 1847. While acknowledging that the move would have little fiscal impact, he thought it was important for the “shock value.” The point to be made was the 1960s were over. No more wine and roses for the common folks, though there was plenty for Felix and his friends—more than ever before, in fact.

Having transferred his skills at financial engineering to the public sector, creating a prototype for debt-driven austerity programs over the next couple of decades, Felix—who had made a banking career of putting together pointless conglomerates like ITT, earning fees that were the envy of his peers—often took to the pages of The New York Review of Books to criticize the financial mania of the 1980s. His own part in this history was never noted in his contributor bio. As Michael Thomas, the ex-banker turned writer (who appears in the film), once told me, “Felix pounds the pulpit with one hand and endorses checks with the other.” I wouldn’t expect Felix’s son to include a detail like that, but that’s why he’s not the right person for the job.

Yes, the national political environment was changing, Reagan would soon come into office and greed would be pronounced good. But a little before him came Paul Volcker at the Federal Reserve, who drove up interest rates toward 20 percent, created a deep recession, and smashed all notions of working-class solidarity or confidence. Volcker was a Democrat, appointed by the Democrat Jimmy Carter. Ed Koch, who was New York’s mayor from 1978 to 1989, turned the fiscal crisis austerity program into the normal mode of urban governance; he was a Democrat, too. And then, with the lower orders fully suppressed, Koch got to preside over a glorious bull market and the gentrification that still dominates New York real estate.

There are entertaining bits in Drop Dead City, and I, who’ve been following this story for a long time, learned some things, from it. But it would be terrible if the film allowed anyone to forget that austerity has been a bipartisan enterprise all along.

Every day, The Nation exposes the administration’s unchecked and reckless abuses of power through clear-eyed, uncompromising independent journalism—the kind of journalism that holds the powerful to account and helps build alternatives to the world we live in now.

We have just the right people to confront this moment. Speaking on Democracy Now!, Nation DC Bureau chief Chris Lehmann translated the complex terms of the budget bill into the plain truth, describing it as “the single largest upward redistribution of wealth effectuated by any piece of legislation in our history.” In the pages of the June print issue and on The Nation Podcast, Jacob Silverman dove deep into how crypto has captured American campaign finance, revealing that it was the top donor in the 2024 elections as an industry and won nearly every race it supported.

This is all in addition to The Nation’s exceptional coverage of matters of war and peace, the courts, reproductive justice, climate, immigration, healthcare, and much more.

Our 160-year history of sounding the alarm on presidential overreach and the persecution of dissent has prepared us for this moment. 2025 marks a new chapter in this history, and we need you to be part of it.

We’re aiming to raise $20,000 during our June Fundraising Campaign to fund our change-making reporting and analysis. Stand for bold, independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Deporting people to countries where they might be tortured or killed? All good, according to the six GOP justices.

In Eugene, Oregon, CAHOOTS, a decades-old crisis-response program, may disappear, but the programs it inspired have spread across the United States, including to nearby Portland.

A grant-supported program found success transitioning young people connected to gangs into higher education—until the money stopped coming.

Former Cincinnati Reds player and manager Pete Rose represents a poisonous form of masculinity that should be rooted out, not beatified.

In the streets, in our legislatures, and in the courts, political leaders are calling for law and order, ignoring the fact that it is their officers wreaking havoc.