The mayor, the governor, and the members of the city’s big-ticket tax base are all squaring off over prospective tax increases and service cuts.

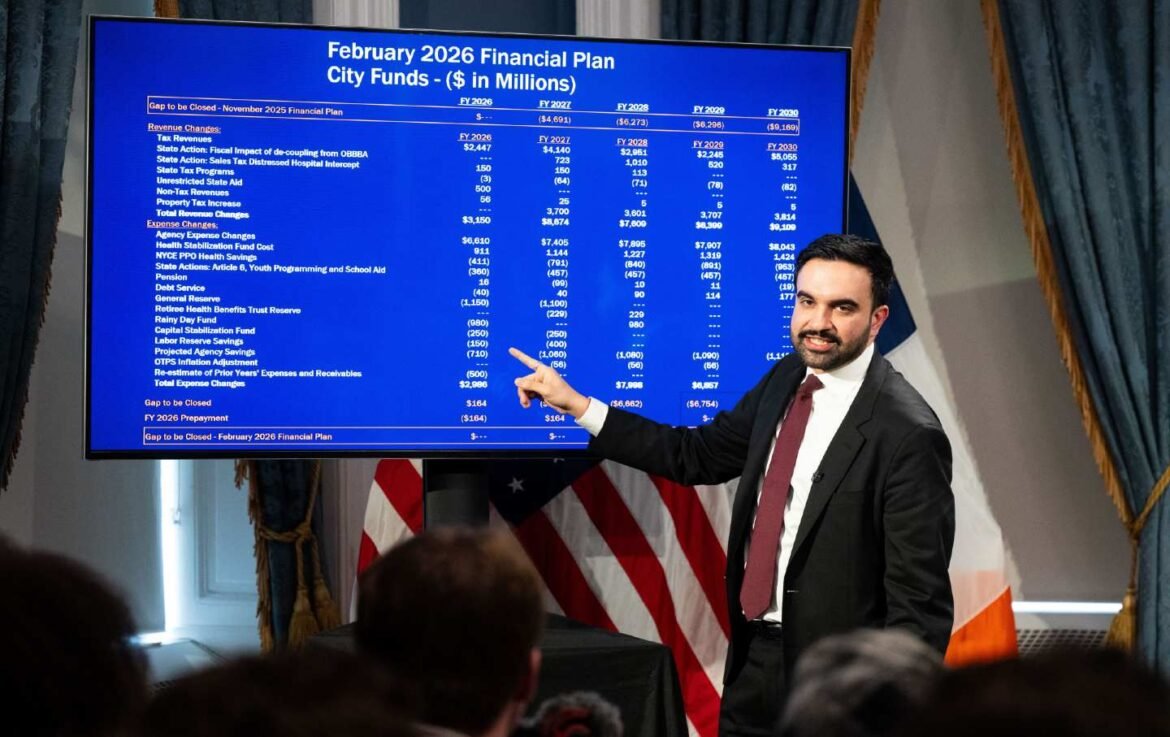

Mayor Zohran Mamdani presents his preliminary city budget at a City Hall meeting.

(Michael Brochstein / Sipa USA via AP)

Judging by Mayor Zohran Mamdani’s performance in City Hall’s Blue Room on Wednesday, there are certain features of New York’s fiscal follies that have changed little during the last several decades.

“Over the last year, New York faced a historic fiscal crisis…” Although that sounds like Mamdani, who used the same phrase to describe the city’s current budget challenges, it was actually former Governor Basil Paterson averting doom back in 2009. When David Dinkins took office in 1990, he, too, inherited a fiscal crisis, as did Rudy Guiliani, who had to close a projected gap of $2.3 billion—out of a total of $31.6 billion—in his first year.

Viewed historically, especially in the context of a total budget of $127 billion, the city’s current $5.4 billion projected deficit—already down from the $12 billion announced a few weeks ago—looks less like a fiscal chasm and more like a pothole. Yet the demands of custom, when coupled with the young mayor’s evident wish to project the financial sobriety signalled by his dark suits and sombre neckties, meant that the press corps—and their readers, viewers and listeners—were again treated to the latest production in a kind of political theatre that never seems to go out of fashion.

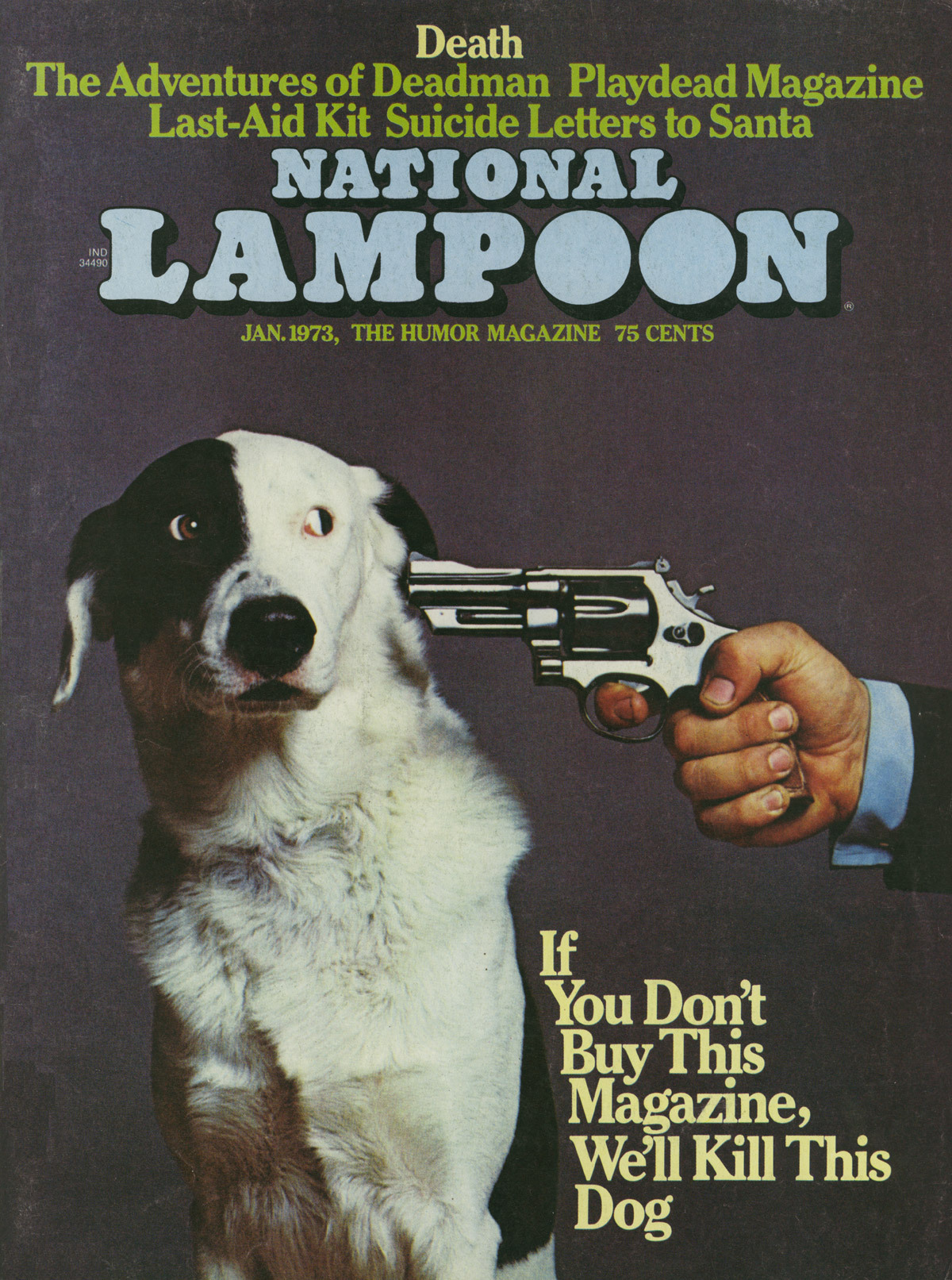

The whole performance is perhaps best summed up by the phrase “or we’ll kill this dog,” an allusion to the classic 1973 cover of the National Lampoon, which threatened desperate measures “if you don’t buy this magazine.”

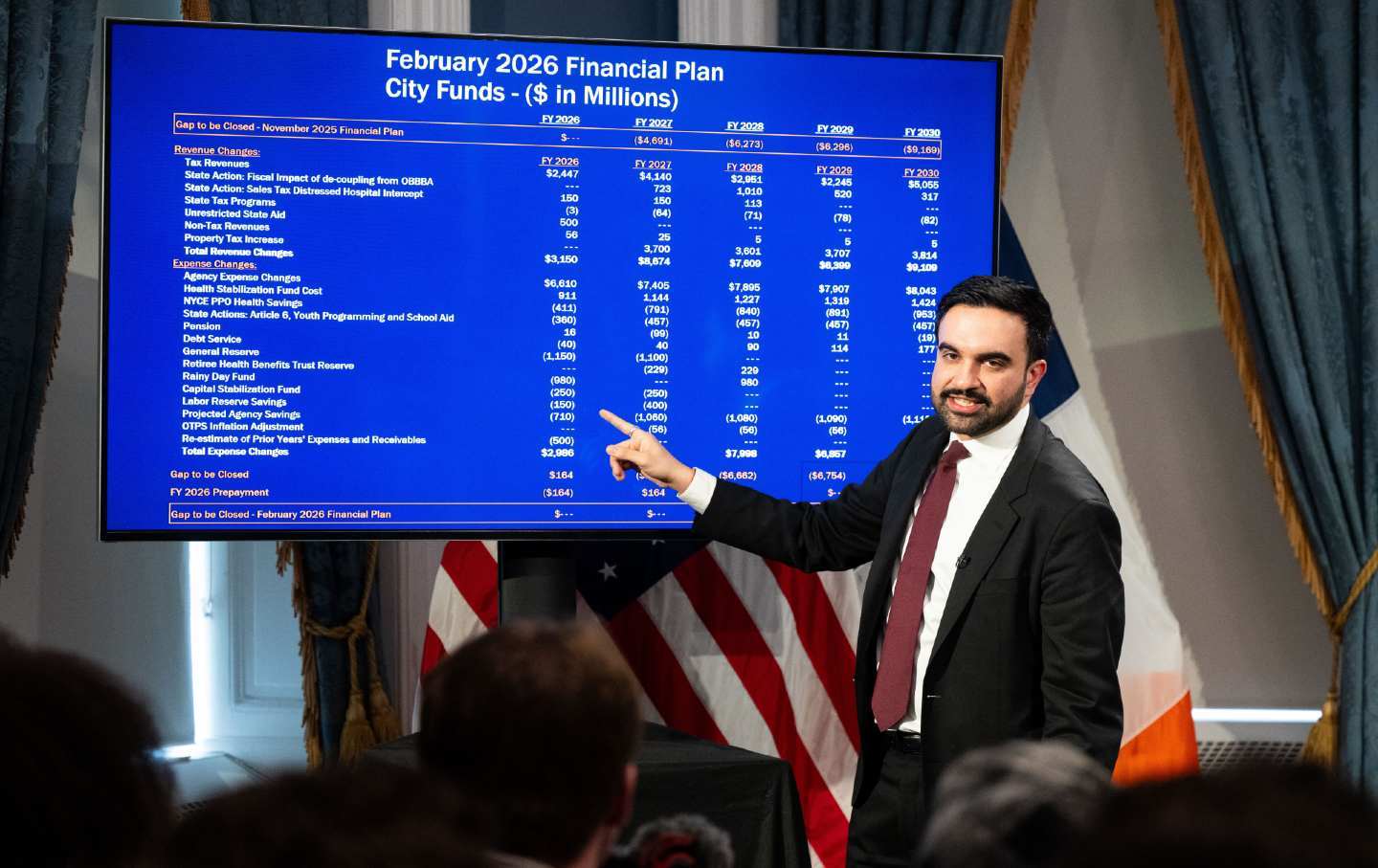

In Mamdani’s case, the threat was to raise the city’s property taxes—which as the mayor noted is the only significant municipal revenue source not subject to the dictates of Governor Kathy Hochul and the state legislature—by 9.5 percent above the current level if Albany continues to balk at the mayor’s preferred policy of a 2 percent increase in city income taxes for New Yorkers earning over $1 million a year and an increase in taxes on the city’s most profitable corporations. The New York Times, The City, Gothamist, Bloomberg and the New York Post all helpfully put the word “threat” in their headlines, with the Post front page depicting a masked and pistol-packing Mamdani ordering the governor to “Stick Em Up!” (Since this was the Post, both of Mamdani’s guns had the red banner of the former Soviet Union peeking out from their barrels. )

There are at least two problems with this perennial pantomime. The first—and given Hochul’s oft-declared reluctance to raise taxes in the midst of her reelection campaign, perhaps the most immediately salient—is that sometimes the other side calls your bluff. Eric Adams, in one of his many borrowings from the Michael Bloomberg playbook, painted a target on the city’s public library system during his 2024 budget negotiations with the city council, only to avert disaster at the last minute. But Dinkins was forced into a hiring and promotion freeze and other austerity measures that accelerated the erosion of city services begun during the 1975 fiscal crisis. (That crisis really was historic, marking the first significant rollback of the La Guardia vision of an abundant public life for New York’s working class and the emergence, at street level, of what would later come to be known as neoliberalism: opportunity and power for the rich, disinvestment and displacement—or as Roger Starr, The New York Times editorial writer who was one of the policy’s chief architects, called it, “planned shrinkage”—for the poor.) Should Mamdani be forced to make good on his threat, the burden would hardly be equitable, since, as The City’s Katie Honan pointed out, “Homeowners in predominantly Black neighborhoods also pay property tax rates that can be double what homeowners in primarily white neighborhoods pay.”

But then it seemed that even as he was uttering the words, the mayor hardly gave them credence. If instituted under the city’s current property tax system, Mamdani’s proposed/threatened hike would only bring in an additional $3.7 billion. (That’s if a pending court challenge to New York’s property tax regime doesn’t produce a verdict declaring it illegal.) The rest of the funds to close the gap would come from a temporary raid on the city’s “Rainy Day” reserves and borrowing from city workers’ pension funds. The city’s workforce numbers around 300,000; adding in the 3 million New York City co-op, condo, and homeowners who would see their tax bills go up, plus tenants in the city’s 100,000 commercial buildings who would likely see their rents rise to cover the tax increase, that’s a lot of hostages to fortune Mamdani is offering to Hochul. The hope, presumably, is that the governor will find a U-turn on taxes less politically painful.

The second problem with this whole drama is that it endlessly defers the hard choices—and political fights—over what kind of city New Yorkers want to live in. To choose one example, the proposed budget includes $543 million next year to help the city comply with a state requirement to cap class sizes at 20 for elementary students and 25 in high schools. That sounds like real money, yet, as Chalkbeat notes, just hiring the 6,000 new teachers needed to meet the state mandate will cost more than $600 million—and that figure doesn’t include funding for additional classrooms or school buildings. (It’s also worth remembering that the Adams administration was able to claim compliance with this mandate only by cooking the figures, declaring thousands of city classrooms exempt from the law.)

The other side of this fight is made up of those who believe, along with the Citizens Budget Commission, that any tax increase “will make the City less attractive for New Yorkers who fund our schools, police, and sanitation—and the businesses that create jobs and support our economy.” They already have their analyses, and their arguments, in place. Instead of cutting class sizes, the CBC helpfully suggests “securing relief from the State class size mandate.” By allowing himself and his administration to be cast in this cheese-paring performance of fiscal rectitude, Mamdani is wasting an opportunity to make the case for the more expansive, more just, more affordable—and infinitely more attractive—vision of city life that he ran on so successfully.

Given the city’s subordinate relationship with Albany, the mayor needs the governor’s support to deliver on that vision. And if this weren’t an election year, the chances of some kind of fiscal compromise would be greater. Given the actual numbers—and the fact that a final budget isn’t due until the summer—the city still might manage to close the gap through a combination of higher-than-anticipated income tax receipts and a small increase in the corporate tax rate.

In the end, though, the mayor’s promise to govern “expansively and audaciously” is simply not compatible with a budget calculated not to panic the bond market—or the governor’s donors in real estate, big tech, or on Wall Street. In the weeks since his inauguration, Mamdani has proven he’s still a world-class communicator, and has (more or less) managed to competently clear the city’s streets after the big snow. What we don’t yet know—but may soon find out—is whether he can fight.

More from The Nation

As Trump continues to dismantle federal agencies, this state shows what happens when a one-party-controlled government makes sweeping public health changes with little resistance….