Portland, Ore.—A few years ago, I showed up to work at Street Roots, a nonprofit street newspaper in Portland, Oregon, where I was the director, and found a man shouting homicidal threats. When our staff called a mental-health crisis line, they were told that the police were on their way.

Oh no.

The man had filled his pockets with rocks from the Willamette River. “This is all I have,” he chanted over and over again.

I was afraid that the police would shoot him if he reached into his pockets. After all, the Portland police—monitored by the Department of Justice since 2012 for use of force against people with mental illness—have shot dead unhoused Portlanders in mental crises many times before and many times after that day. Instead of spending time getting him resources, I talked him through emptying his pockets and keeping his hands visible.

The first-responder system that should be there to help him was putting him in danger. There had to be a better option—and there was.

About 100 miles south of Portland in Eugene, Oregon, a program called CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets) had been operating since 1989. Emergency operators would send unarmed teams of medics and crisis workers to handle calls that would otherwise have gone to the police, such as welfare checks, conflict resolution, suicide intervention, substance use calls. This past year, 17 percent of police calls were diverted from the police, University of Oregon researchers estimated. They also provide non-emergency medicine, reducing ambulance trips to the hospital.

In 2019, Street Roots published a special issue laying out a plan for a similar street-level response team in Portland based partly on CAHOOTS. After publication, unhoused people, community organizers, elected officials, and bureaucrats banded together to pitch and then implement what became known as the Portland Street Response.

In the years leading to the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, CAHOOTS inspired and supported other cities besides Portland. Denver set up the Support Team Assisted Response (STAR) dispatch team and Olympia, Washington, created the Crisis Response Unit (CRU). Anne Larson, who ran CRU until 2022, recalled that when the Olympia police chief arrived having worked in Eugene, one of his first questions was: “Where are the hippies in a van?” Many police leaders wanted these programs, because it made their jobs easier.

When protesters hit the streets after the murder of George Floyd, communities scrambled to figure out who other than police could deal with emergencies, and many looked to CAHOOTS. This is when this first-response model hit the mainstream. The Atlantic, CNN, GQ, and The New York Times all published pieces on CAHOOTS. The Daily Show ran a segment, and the project even received attention from some unlikely outlets: The Soap Opera Spy announced in a headline: “Royal Family News: Prince Harry & Oprah Demand Group Called CAHOOTS Replace Police.”

Oregon Senator Ron Wyden, a Democrat, sought to expand the model, passing the CAHOOTS Act in Congress in 2021 to provide federal funding through Medicaid.

So it was shocking when on April 7, the city of Eugene severed ties with CAHOOTS.

Berkeley Carnine, a CAHOOTS worker who lost their job because of this, told me, “I think there is that sense of astonishment outside of Eugene, of how could Eugene let this happen?”

In June, the city councils of Oregon‘s two largest cities passed budgets that point in opposite directions for their alternative first-response programs: In Portland, additional ongoing general funds for its response team, and in Eugene, zero funding for CAHOOTS. (The Eugene City Council offered a smidgen of hope by budgeting $500,000 to launch a future request for alternative response proposals as well as a budget amendment to revisit funding.)

“CAHOOTS was more than a program; it was a movement to redefine what public safety is,” Portland City Councilor Candace Avalos said. “The confluence of the pandemic and the racial justice uprisings allowed people to stretch their imaginations beyond police.” With the decline of CAHOOTS, she said it was even more important to ensure that the Portland Street Response was a success. “There’s pressure on PSR to be a beacon in this moment, because CAHOOTS is possibly gone. That’s tragic. So much dies on the vine because we refuse to fund the public good.”

How did the 35-year-old relationship between the City of Eugene and CAHOOTS fall apart so disastrously? The answer matters to communities across the nation who describe their aspirational programs as “CAHOOTS-like”—their hope in police alternatives anchored in the fact there’s a precedent. In New York state, in response to the police killing of Daniel Prude in Rochester, campaigners drew from the example of CAHOOTS to develop “Daniel’s Law,” to require communities across the state to respond to mental-health crises with trained mental health workers, peers, and EMTs, not police.

All the national attention on CAHOOTS put an enormous strain on the White Bird Clinic, the organization that ran CAHOOTS. Not only was it in the national media spotlight but civic groups across the country were reaching out for presentations and advice, desperate to learn from the group’s real-world experience. White Bird Clinic had a somewhat horizontal structure and used consensus decision-making. Workers divided up requests via a spreadsheet, and the CAHOOTS operations coordinator, Tim Black, shifted into an outreach role. “It was hard to respond to a tenfold increase in inquiries overnight,” Black told me.

The external attention exacerbated internal tensions for an organization stressed by low wages and the constant need to raise money.

Jo Ann Hardesty, the Portland City commissioner who led the creation of Portland Street Response, admired CAHOOTS but took lessons from its “low pay, high turnover” employment situation. She pushed to create a city program so employees would have “all the benefits that that entails.”

At the heart of the challenges, Eugene covered only about 40 percent of the costs of running CAHOOTS, said Justin Maderia, a CAHOOTS coordinator. White Bird tried to fill the gaps with grants and donations for both CAHOOTS and its other programs, some of which lost federal funding sliced by the Trump administration.

Last March, White Bird announced a 90 percent reduction in CAHOOTS services—collapsing what had been a 24-7 response to one eight-hour shift. White Bird couldn’t afford to run the vans any longer, and what it could offer wasn’t enough for the city.

“We mutually agreed they would just withdraw from the contract,” said Eugene deputy fire chief Chris Heppel, who managed the CAHOOTS contract for the city.

When I pressed Heppel on why Eugene didn’t pay fully for CAHOOTS services, he said, “We put out the contract and that was the contract they signed. They didn’t come back and ask for more money.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Madeira argued that the White Bird should have negotiated a better contract with the city of Eugene, particularly after staff unionized and raised employee wages.

But this challenge reveals a larger problem across governments: Nonprofit organizations are often contracted to provide cheaper labor, and the onus is on nonprofits to scramble to make ends meet.

White Bird started in the late 1960s by providing counterculture medical care, staying alongside people having “bummer” psychedelic trips. White Bird workers brought together medical and mental-health care for people who were uninsured and otherwise not well-served by conventional systems. They also provided “rock medicine”—setting up clinics at rock festivals and the Oregon Country Fair, the enduring art and music festival outside Eugene that was a stop-off for Ken Kesey and his band of Merry Pranksters as well as the Grateful Dead. After years of running a “bummer van” to pick up people struggling from the effects of drugs and alcohol, the “fairly anarchist group of hippies”—as CAHOOTS cofounder David Zeiss described early CAHOOTS workers—entered into an agreement with the police to take over some of their calls for service.

They were officially in “cahoots” with the police, as the radical organizers playfully named what they were doing.

The key part of the CAHOOTS project was using 911-dispatch to shunt noncriminal crises away from the police. But there are also other elements at play when programs are described as “CAHOOTS-like.”

“It’s holistic, it’s patient-, it’s client-led, noncoercive,” Michelle Perin, a CAHOOTS worker laid off when the Eugene contract collapsed, told me.

“We’re not guts and glory. We’re diabetes and scabies,” quipped Manning Walker, a former CAHOOTS medic who has gone on to help start CAHOOTS-like programs in California.

A number of fire bureaus have incubated alternative response programs over the last several years because they are involved in medical services—and separate from the police.

That’s how Hardesty started Portland Street Response. Until 2025, city commissioners oversaw city bureaus. Portland Street Response was first piloted in the fire bureau overseen by Hardesty, and then the subsequent commissioner, Rene Gonzalez.

Elected in 2019, Hardesty worked to build out Portland Street Response to survive beyond what turned out to be one action-packed term. The first Black woman to serve on the Portland City Council, Hardesty weathered relentless violent and racist threats, and the local newspaper, The Oregonian, ran an unverified story that she was responsible for a hit and run. (She wasn’t.) She successfully sued the police union for planting the story. It was in this political climate that Gonzalez, running as a law-and-order candidate, beat Hardesty in 2022.

As commissioner, Gonzalez dismantled some of his predecessor’s achievements, freezing hiring for the Portland Street Response in 2023, banning the distribution of tents and other supplies in the rainy winter, and claiming that responding to the homelessness with care work was “enabling” people.

On a recent Friday afternoon, Angela Sands, a Portland Street Response crisis responder, explained to me how important providing supplies is for the work they do. “When you have someone on the sidewalk who hasn’t eaten in days and maybe has an open wound that’s infected, being able to stabilize them in the moment—giving someone something to eat, something to drink—can completely change their day. I’ve seen people go from suicidal to not just with some basic needs met.”

But Gonzalez challenged these de-escalation strategies, and only two years ago, it wasn’t clear if Portland Street Response would survive.

Yet Portland Street Response was popular. In response to Gonzalez’s clampdown in the summer of 2023, Friends of Portland Street Response (which I helped start) collected more than 10,000 signatures in a week, demanding that the city save and strengthen the program.

An independent evaluation from Portland State University revealed clashes between the top-down, often macho fire department culture and a growing culture of care work that brought in tools from social work and organizing. In 2024, then-Mayor Ted Wheeler helped stabilize Portland Street Response by moving it from the fire department to the newly created Community Safety Division.

While Portland Street Response was no longer administered by the fire department, CAHOOTS now was. The Eugene city manager moved it from under the police department to under fire in 2023. This was not a drastic change—the same 911 system continued to dispatch them. But because of its medical services the fire department had started to develop its own “alternative response” initiatives, and Lane County—which surrounds Eugene, Springfield, and other nearby towns and rural communities—launched Lane County Mobile Crisis Services teams, as mandated by the Oregon legislature.

By the time I spoke to Hemmel, he described the work of CAHOOTS as outreach to homeless people, an attenuated view of CAHOOTS, which was historically dispatched inside residences as well. In some ways, the success of CAHOOTS weakened its own role: The expanding field of alternative response meant more people were receiving services without facing down the police first. CAHOOTS, which never fit neatly into government structures, was considered less necessary.

Even the CAHOOTS Act was too restrictive for CAHOOTS, because the bill required professional qualifications, whereas CAHOOTS has long championed using peer responders.

I asked Senator Wyden what he thought of the demise of his bill’s namesake. “While a setback in any one local mobile crisis response system is of course disappointing,” Wyden wrote me, “the fundamental strength and wisdom of the mobile crisis response model remains a proven approach to save lives on the street.”

Under the Trump administration, even if alternative first-response programs can access Medicaid funding, it might not bring them stability. DOGE has ransacked Medicaid funds, and Trump’s horrifying “Big Beautiful Bill” could further sabotage Medicaid.

While the 2020 protests sparked the proliferation of alternative response programs, the federal response to Covid-19 through the American Rescue Plan funds helped many get off the ground, explained Scarlet Neath, who leads research on this growing movement for New York University’s Policing Project. Now alternative response programs need consistent funds. That’s why Local Progress, which organizes elected leaders at the local level on progressive causes, recommends setting up city programs, said Reynold Graham, who runs the public safety program.

This is where Portland Street Response has turned the corner. The Portland City Council voted in a budget that funds Portland Street Response through its ongoing general funds.

The newly elected mayor of Portland, Keith Wilson, increased the budget for Portland Street Response when most other budgets were reduced or frozen to address a deficit. Wilson explained to me that this “investment in Portland Street Response must come as part of a holistic approach to restoring public safety.” But currently the budget still doesn’t support running it 24-7—a prerequisite to qualify for Medicaid funding under the CAHOOTS Act.

Now, on June 25, the Portland City Council is poised to strengthen Portland Street Response further with a vote on a resolution to commit to funding Portland Street Response to running 24-7—inching it closer to eligibility for federal funding—and develop it into a coequal branch with fire and police.

The resolution maintains the Portland Street Response as noncoercive, a common principle of programs across the country but one that needs consistent defense, particularly as many cities double down on camp sweeps after the Supreme Court decision last summer that created more leeway to do so.

“We have this game-changing resolution that will be a defining moment for Portland to change what community safety looks like,” said Avalos, who cosponsored the resolution with Councilors Sameer Kanal and Angelita Morillo. The vote will be close.

Half of the current City Council campaigned on the issue of strengthening Portland Street Response. It is better supported after Portland voted in a new form of government—where councilors no longer run bureaus and there’s proportional ranked-choice voting with 12 city councilors elected across four districts.

“People figured out that actually district-based proportional representation is meaningful,” Councilor Mitch Green told me. “And the outcome of that is we actually did elect a slate of progressives.” Green is one of four members of the Democratic Socialists of America on the Portland City Council. He introduced successful budget amendments to set aside funds for evaluation as well as move $2.2 million from the police budget to any public safety program—including Portland Street Response—that needs to expand capacity. (The Portland Police Bureau currently has 84 vacancies for its approved budget, so, in effect, the city’s police presence will not be decreasing.)

What happens next in Eugene? CAHOOTS itself might still have a comeback. While White Bird is considering applying for future contracts, it still is running vans in neighboring Springfield, which reimburses the nonprofit at a much more sustainable level. A group of current and past CAHOOTS workers have also filed to start a new nonprofit, Willamette Valley Crisis Care, which they refer to as “CAHOOTS 2.0.” Additionally, some Eugene City Council members have suggested making a “CAHOOTS-like” city program to extend city wages and stability to the crisis workers.

Will White Bird rebuild or the new worker nonprofit contract with Eugene? Or will CAHOOTS continue on only through its legacy, like the Freedom House in Philadelphia, which inspired the modern ambulance system in the 1960s?

That would be a loss to Eugene. By focusing on a noncoercive, holistic approach, CAHOOTS showed up to many undefined, non-emergency crises. The Lane County Crisis Response is set up for acute mental-health crises, but the less defined crises such as welfare checks’ being routed back to the police.

Five of the workers who are attempting to create a CAHOOTS 2.0 talked with me about the community support they have for the project and how momentum built after a town hall with the University of Oregon.

While they worry about all the people who aren’t receiving services—CAHOOTS was responding to more than 40 calls per day—the workers are doing what they know how to do: respond to a crisis. But this time it’s their own. They are now the ones who need help. As Berkeley Carnine, one of the former CAHOOTS workers building the new nonprofit, put it, “We’ve been able to come together and make these relationships and give community an outlet to turn out for us.” That community pressure has mattered. The City Council is now instructing the city manager to locate funds for “CAHOOTS-like services” in the future. Even Eugene, the originator of CAHOOTS, is seeking to emulate CAHOOTS.

Every day, The Nation exposes the administration’s unchecked and reckless abuses of power through clear-eyed, uncompromising independent journalism—the kind of journalism that holds the powerful to account and helps build alternatives to the world we live in now.

We have just the right people to confront this moment. Speaking on Democracy Now!, Nation DC Bureau chief Chris Lehmann translated the complex terms of the budget bill into the plain truth, describing it as “the single largest upward redistribution of wealth effectuated by any piece of legislation in our history.” In the pages of the June print issue and on The Nation Podcast, Jacob Silverman dove deep into how crypto has captured American campaign finance, revealing that it was the top donor in the 2024 elections as an industry and won nearly every race it supported.

This is all in addition to The Nation’s exceptional coverage of matters of war and peace, the courts, reproductive justice, climate, immigration, healthcare, and much more.

Our 160-year history of sounding the alarm on presidential overreach and the persecution of dissent has prepared us for this moment. 2025 marks a new chapter in this history, and we need you to be part of it.

We’re aiming to raise $20,000 during our June Fundraising Campaign to fund our change-making reporting and analysis. Stand for bold, independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

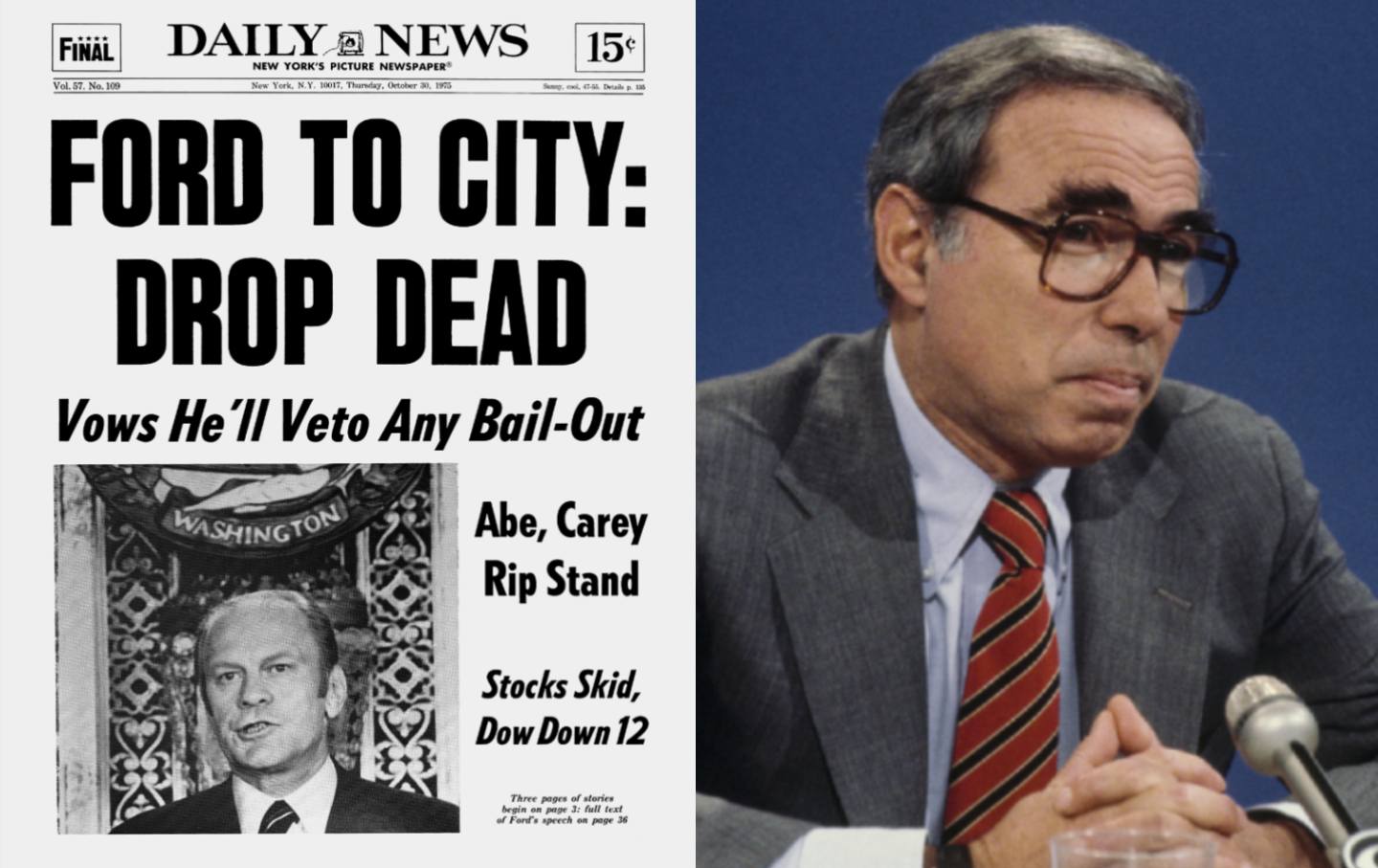

A new documentary about the 1975 fiscal crisis, Drop Dead City, is entertaining to watch but dangerously misleading as history—or politics.

A grant-supported program found success transitioning young people connected to gangs into higher education—until the money stopped coming.

Former Cincinnati Reds player and manager Pete Rose represents a poisonous form of masculinity that should be rooted out, not beatified.

In the streets, in our legislatures, and in the courts, political leaders are calling for law and order, ignoring the fact that it is their officers wreaking havoc.

The ownership turned ICE away at the stadium and pledged $1 million to families of immigrants because of all the people protesting Trump’s immigration actions in LA.