As an undergrad, I mocked the radical leftist turned reactionary. But with his cruel, vindictive politics taking over the government, he had the last laugh.

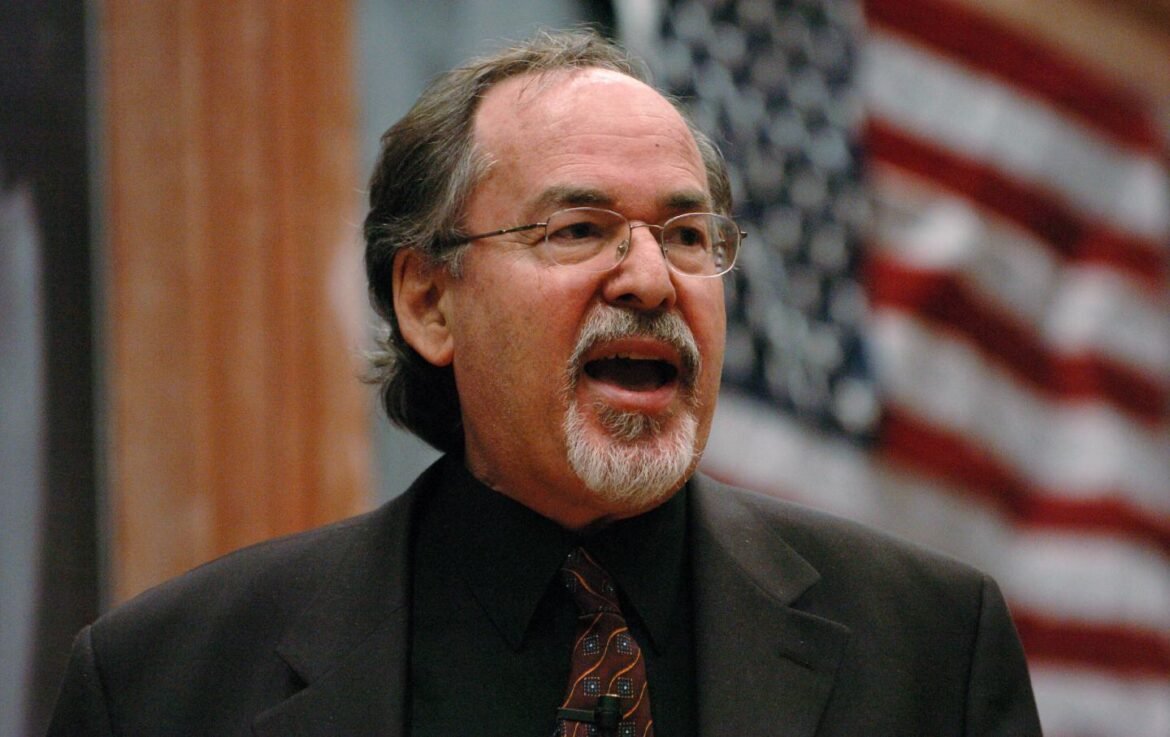

David Horowitz, who died in April, spoke on the CU Boulder campus on February 14, 2005, about what’s wrong with various professors in US universities today.

(Brian Brainerd / The Denver Post via Getty Images)

The first time I thought about David Horowitz was in 2006, when I was a 22-year-old senior at Horowitz’s alma mater, Columbia University. A friend—like me and Horowitz, a Jewish David—had commissioned me to review Horowitz’s latest book, The Professors: The 101 Most Dangerous Academics in America, for the Columbia Political Review. As a snotty undergraduate, I agreed to do so on the condition that I wouldn’t have to read the book and that I would admit that I hadn’t upfront. Rather than an actual review, I wrote a generalized attack on Horowitz as a “once-radical hack,” accusing him of producing a McCarthyist screed and of libeling nine Columbia professors among his chosen 101—but I also reduced his life, or what I assumed without any research to be the broad outlines of his life, to a cliché:

I think I’ll use this review as a chance to publicly denounce Horowitz with the same shoddy scholarship and borderline-racist vitriol to which he routinely subjects his far more impressive targets. Horowitz was born, I would estimate, sometime during World War II. He probably grew up somewhere within ten miles of Morningside Heights. He is probably a second- or third-generation American, which, to my mind, has awfully suspicious implications. His parents, I would imagine, were Stalinists, but eventually recanted sometime around the revelation of the Doctors’ Plot and became Trotskyists instead, probably while Horowitz was in his Portnoy phase.

Horowitz may have socialized with Irving Kristol and Norman Podhoretz at some point in his career. There is a good chance he protested the Vietnam War and ROTC. Then, sometime between 1968 and 1979, he realized that he hated Arabs and Black people. Coincidentally, he also realized that the free market works after all. Then he probably voted for Reagan.

It’s embarrassing to revisit some of my earliest writing, but still, I was pretty close. Horowitz was born in January 1939, eight months before World War II broke out in Europe (arguably, it had already begun in Asia). He grew up in Sunnyside, Queens, about five miles from Morningside Heights as the crow flies. He was indeed a second-generation American on both sides, and his parents really were Stalinists, though it was Nikita Khrushchev’s “secret speech” in 1956 rather than the earlier Doctors’ Plot that broke them. He did at some point socialize with Kristol and Podhoretz, he did protest the Vietnam War (not sure about ROTC), and the rest of that second paragraph is essentially accurate too.

In the nearly two decades since I wrote that, I’ve learned a great deal more about the history of conservatism, and these days I always do the reading. When Horowitz died at 86 last month, I assigned myself Radical Son, his 1997 autobiography, widely regarded as the most essential text among the roughly 60 books he wrote or cowrote. I now see that in some ways I was underestimating Horowitz—to my shock and chagrin, the eventual author of books like Blitz: Trump Will Smash the Left and Win (2020) and I Can’t Breathe: How a Racial Hoax Is Killing America (2021) had actual prose chops and a deep knowledge of 20th-century political thought. At one point, he was capable of writing a moving memoir about radicalism and disillusionment, suffused with generational pain, candid self-examination, and indelible portraits of former comrades. I was also unfair in classifying Horowitz as a “neoconservative,” a term bandied about often in 2006; though in some ways his life followed similar beats, he also differed from the foundational neocons in significant and telling ways. But perhaps most of all, I was unfair in dismissing him as an inconsequential figure. Unfortunately, he turns out to have been ahead of his time.

If Irving Kristol is the paradigmatic neoconservative, the consistent through line that defines every stage of his ideological journey is anti-Stalinism. As a teenager, he was a Trotskyist; by his 20s, he was a Cold War liberal, and at middle age, he shifted toward the party of Nixon and Reagan, but his opposition to Stalinism was consistent, and it was the basis for his antagonism toward the New Left that arose on college campuses amid the counterculture of the 1960s. To Kristol and his cohort of ex-Trotskyists, the radical moral fervor of the New Left was a frightening echo of the dogmatic communists they had clashed with back in the 1930s.

David Horowitz, who was 19 years younger than Kristol, had a strikingly different journey. He was raised by Stalinists of roughly Kristol’s generation (like Kristol, Horowitz’s parents were the New York–born children of Russian Jewish immigrants) who experienced McCarthyist repression firsthand, which meant that Horowitz himself, a self-described red-diaper baby, grew up under a cloud of political suspicion. Horowitz went on to become centrally involved in the New Left, and he knew all its most prominent figures, from Tom Hayden to the Black Panthers. Based in Berkeley at the height of the counterculture, Horowitz was the co-editor of Ramparts, a radical magazine that represented everything Kristol and his fellow neocons hated. And while much of the neoconservative movement is now defiantly anti-Trump (Irving Kristol died in 2009, before Donald Trump ever ran for office, but his son Bill is the quintessential Never Trumper), Horowitz embraced MAGA populism.

In short, Horowitz started out much further left and ended up much further right than most neoconservatives ever did. The story of how that transition happened was also far more dramatic. The neocons, broadly speaking, moved right beginning in the late 1960s because they were troubled by the unrest that they saw on college campuses and in urban slums; at the time, Horowitz was very much part of that unrest. His transition came in the mid 1970s and was triggered, at least in his telling, by a traumatic incident: the unsolved murder of his friend Betty Van Patter. Van Patter had been the bookkeeper at Ramparts when Horowitz recommended her for a similar role for the Black Panther Party in Oakland, where Horowitz was helping Huey Newton establish a school. She mysteriously disappeared at the end of 1974, and her battered corpse turned up in the San Francisco Bay over a month later.

Horowitz believed the Panthers had his friend murdered and that the New Left writ large ignored her fate out of deference to the Panthers, and he became overcome with guilt over his personal complicity. Though it took another decade for Horowitz and his frequent co-author Peter Collier to “come out” as Reaganite conservatives and another decade after that for Horowitz to fully reflect on his story in Radical Son, Van Patter’s death marked the beginning of the end of Horowitz’s relationship with the left. To the extent that we can trust his own account, nothing less than a woman’s life had been sacrificed to his misguided ideals. He sank into a depression, and by the time he emerged, he had concluded that Marxism, along with all of the revolutionary causes that had defined his life to that point, was false.

That revelation hits around the halfway point of Radical Son, which up until around there is a gripping account of a life on the American left. After that, Horowitz’s life starts to deteriorate, as does the quality and coherence of the book itself. Having destroyed his first marriage, which produced four children, in a reckless affair, Horowitz proceeds to cycle through two more chaotic and ill-considered marriages (the fourth one stuck). As he alienates old friends, he passes through the stages of a classic midlife crisis: new vanity car (which he crashes), new vanity home, new and increasingly half-baked political positions, and a growing closeness with right-wing donor networks. As he sets down to record all this in the mid 1990s, his transformation into a Republican demagogue is complete. Thus, by the time I became aware of him a few years after the publication of Radical Son, he was hounding college professors in a farcical reenactment of the McCarthyist persecution of his parents, and he was recruiting young conservative demagogues on those same elite campuses and funneling them into careers on the professional right.

In hindsight, the most influential figure Horowitz nurtured in that period was a student at Santa Monica High named Stephen Miller, who even as a teenager had begun making regular appearances on right-wing talk radio in Southern California. Horowitz helped steer Miller to Duke University, where Miller established a branch of Horowitz’s nonprofit empire, now called the David Horowitz Freedom Center, which the Southern Poverty Law Center recognizes as an anti-Muslim hate group. With the benefit of Horowitz’s patronage and tutelage, Miller became an outspoken reactionary at Duke during the George W. Bush years, and Horowitz further helped him land his first Capitol Hill job, which set him on the path to become one of Donald Trump’s top advisers. Today, Miller is the single figure most associated with Trump’s brutally repressive deportation policies, including how those policies have been used to terrorize and imprison campus activists without due process.

Horowitz’s impact also extends to another part of the Trump coalition: the clique of Silicon Valley oligarchs who funded Trump’s victory last year and now expect fealty to their business interests, which encompass AI, cryptocurrencies, and monopolistic disruptions of traditional sectors. A key figure in that world is Horowitz’s son Ben Horowitz, who along with Marc Andreessen founded the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz (a16z) in 2009. Andreessen and Horowitz each donated $2.5 million to pro-Trump Super PACs last year (though Horowitz also gave to Bay Area native Kamala Harris, whom he’s known for years, presumably to hedge his bets), and after Trump won, Ben Horowitz proclaimed, “Hallelujah!” on the a16z YouTube show. He and Andreessen agreed that Joe Biden’s attempts to regulate the tech industry represented a low point in their industry’s fortunes, and they were overjoyed at the prospect of a president who would, as Andreessen put it, remove the boot from their neck.

To the extent that Stephen Miller and Ben Horowitz represent his legacies, David Horowitz is a forerunner of the Trump coalition, with its grotesque alliance of fever-swamp nativists and Bay Area plutocrats. Twenty years ago, he was regarded as something of a clown and a provocateur, rather than a serious conservative intellectual, even if his earlier career had shown intellectual promise. But today’s Republican Party is far more in line with the vindictive style of Horowitz than with what The Weekly Standard was publishing back when George W. Bush was trying to make “compassionate conservatism” a thing. As an undergraduate at Columbia, I considered Horowitz a joke, but 500 miles to the southwest, another undergraduate saw him as a career guru. Today, that guy has the power to rip apart immigrant families anywhere in the United States out of sheer malice, and all I have is a magazine column.