In May of 2023, Ozaa Echo Maker heard a group of people knock at her door and didn’t answer. “I didn’t want to talk to any of them,” she said. “I was scared and socially awkward.”

The visitors were organizers from Bozeman, Montana’s citywide tenant union, conducting one of their regular canvasses of local apartment complexes. After it became clear that Echo Maker wasn’t coming to the door, the group moved across the hall and began speaking with Echo Maker’s neighbor. Echo Maker overheard them talking about organizing through their tenant union, a term she had never heard before. The closest she’d ever come to organizing was building a float for her high school’s homecoming parade.

Hearing them, she thought, “I was like, you mean me complaining about my circumstances can actually be more than just complaining?” Echo Maker told me. “I can complain with a purpose?”

Echo Maker has been a tenant all her life. For the last six years, she’s been back in the same unit she lived in with her mother after she was born, in a complex called Bridger Heights that houses low-income tenants across 50 units. But in 2019, the property was bought by a new real estate investment company, who she says have proven themselves to be absentee landlords that allow poor conditions to go unaddressed. Echo Maker contracted a severe neurological disability 10 years ago, and for years that in combination with the worsening conditions left her spending the bulk of her time on “survival mode.”

This August, however, she told a different story. On the Zoom call that officially launched the new national organization the Tenant Union Federation (TUF), she announced a new identity: a leader of Bozeman Tenants United, the very same union for whom she’d been scared to answer the door.

TUF, made up of local member unions Bozeman Tenants United, KC Tenants in Kansas City (Missouri), the Louisville Tenants Union, the Connecticut Tenants Union, and Not Me We in Chicago, is the first major tenant organizing effort with a national structure to emerge in decades. Prior to its official launch, TUF had already been an instrumental force in the campaign that pushed President Joe Biden to propose federal rent control in July. Its member unions are collectively bargaining leases, working to put tenant organizers into elected office, and fighting successfully for laws to prevent gentrification, all in the name of establishing renters as a formidable political class.

As TUF is finding its national footing, many of its leaders are tenants like Echo Maker, fighting to directly improve their own living conditions. Many are low-income and disabled, unable to work traditional jobs and therefore living off meager Social Security payments. They often live in run-down, neglected buildings often explicitly reserved for elderly and disabled tenants, who are typically the most vulnerable to exploitation from their landlords. And each of them—from Echo Maker to Lori-Lynn Ross in Connecticut to Donna Goldsmith in Louisville—considered themselves completely alienated from not just the political process but their own communities as well, before TUF organizers knocked on their doors.

“I think people’s intuition about collective power is already there,” Tara Raghuveer, TUF’s founding director, told The Nation. “What makes the difference is really the invitation. For many, this is the first invitation into something like this they have ever received.”

In America’s commodified housing market, people are not socialized to be proud to be tenants in the way that they are to be homeowners. Where “worker” is and has increasingly become an identity of pride, helping fuel a resurgence of labor organizing, “tenant” may suggest insufficiency, or at least, impermanence.

That’s why, Raghuveer said, it’s crucial that these leaders are using organizing to develop a new sense of strength within themselves and in others. Perhaps no one exemplifies this metamorphosis more than Echo Maker, who in less than two years has gone from being completely detached from politics and movements to being selected to serve on the Federal Advisory Committee on Affordable, Equitable, and Sustainable Housing, in addition to organizing her Bozeman neighbors.

“I’m becoming the type of role model I wish I had,” Echo Maker said. When I spoke with her in September, her 5-year-old daughter was about to start kindergarten. “She is always telling people, ‘My mom works at the tenant union.’ That’s how I know I’m doing a good job as a parent. When my kid grows up, she’s going to see things wrong in the system and go, ‘Oh, no way.’”

Over the last six years, Echo Maker has lived at Bridger Heights, she has watched the property crumble around her.

The building is nearly 50 years old and increasingly vulnerable to rainstorms. Water damage has led to health hazards like black mold; Echo Maker’s ceiling has started to bubble and crack. The building’s more than 50 residents share only a handful of washers and dryers that leave clothes damp. A first-floor window has been broken for months, leaving a jagged hole that any of the complex’s young children—including Echo Maker’s daughter—could accidentally tumble into. Management rarely, if ever, answers the phone.

In 2013, Echo Maker was an undergraduate at Montana State University and suddenly began having constant seizures. She ended up bedridden for six months and had to drop out. Now, her seizures aren’t as frequent, but they still leave her unable to work a traditional job and reliant on federal disability assistance. Moving into Bridger Heights was a victory for her, as her unit is federally subsidized, meaning she can afford to pay rent without getting a job. But as the building’s conditions rapidly worsened, it also meant that she was essentially trapped—wait times for these types of apartments can last years, so Echo Maker can’t easily move to a better-managed building.

When the tenant organizers knocked in 2023, Echo Maker told me, she was severely depressed and doubted her ability to effect change. But after listening through the door, she decided to give the union a chance, paying a visit to the first of what would become many tenant organizing meetings.

For Echo Maker, these meetings were her first opportunity to be part of collective action. “You can’t be in a labor union unless you actually work,” Echo Maker said. “I can’t. But [at the meeting], they said, ‘One of our principles is that your value is not based on whether you contribute to society financially.’”

Tenant leaders like Echo Maker, Raghuveer said, are a reminder that, even as labor organizing is seeing a seismic upsurge, the “vast, vast majority of the population is not and has not ever been part of a labor union or any powerful collective.”

Part of TUF’s work, then, has been providing a venue to bring new or underrepresented groups into the fold.

“In my experience, where organizing begins to fail is when it doesn’t center directly affected people, when it becomes professional staff making healthy salaries and who aren’t affected by their issue anymore,” Joey Morrison, one of the founders of Bozeman Tenants United who last fall was elected to become the city’s next mayor, told The Nation. “Tenant organizing is explicitly centering people who are struggling.”

Over the next few months, Echo Maker was swept up in organizing projects of increasing responsibility, from canvassing to meetings with Bozeman city commissioners. The union kept extending the invitation, and Echo Maker kept saying yes.

Next thing Echo Maker knew, it was November and she was flying to Washington, DC, with a tenant delegation set to meet with senior policy analysts at the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) to push the agency use its power over rental properties receiving federal mortgage assistance—which includes some tens of millions of units—to enact rent control, along with other tenant protections (several of which the FHFA has since enacted). Biden would eventually propose a less ambitious version of TUF’s rent cap proposal in July. (Come January, the chances of the federal government signing off on rent control will all but vanish, as Donald Trump, arguably one of the most infamous landlords in the world, will once again be the president.)

Echo Maker said the trip left her with a newfound sense of political power.

“When I told [lawmakers and their staff members] I was a disabled solo parent, they were taken aback,” Echo Maker said. “A lot of times, people in positions of power are so far removed from the problem that they can only theorize about what it’s actually like to live in a property like mine. I have 24/7 lived experience. So it was a moment of realizing that I have power. I can make them sit down and listen to me.”

Donna Goldsmith, a 63-year-old disabled leader with the Louisville Tenants Union, has embarked on a similar path. Like Echo Maker, she lives on Social Security, having developed severe arthritis on top of still bearing scars from an intense knee surgery and cancer battle. She grew up “dirt-poor” and until recently lived in a corporate-owned complex for the elderly and disabled that has constant plumbing issues and, as in Echo Maker’s building, rampant mold. Like Echo Maker, she never had much interest in, or even knowledge about, organizing. But since tenant union members came knocking, she’s found a way to do it anyway. Her union has managed to force the city’s housing authority to cut ties with a negligent property management company and got an ordinance that prevents developers from getting tax dollars for projects that push out existing residents in favor of new wealthier ones unanimously passed by Louisville Metro Council. These wins are on top of the union’s current campaigns to win collective leases at multiple large complexes.

“I enjoy canvassing [for the union],” Goldsmith said. “Sometimes I can’t go up the steps, but I can still get the bottom apartments. Just go out and do what you gotta do.”

“There’s this Michael Jackson video, ‘Billie Jean,’ where the ground lights up whenever he puts his foot down,” Lori-Lynn Ross, a 57-year-old tenant in Branford, Connecticut, who serves as a chapter vice president in the statewide Connecticut Tenants Union (CTTU), said. “The union has become that [path] for me.”

Since 2008, Ross has lived in a large complex owned by the Branford Housing Authority but managed by a private management company, and describes living under constant “neglect” and “abuse.” She reports that the residents, all of whom are low-income and either elderly or disabled, frequently have no heat. The regularly broken elevators force residents in wheelchairs to be carried up the stairs. In 2021, Ross’s unit flooded after a storm created a water leak, in which she lost “everything,” including Bibles that had been in her family for generations. She says management only recently finished making the needed repairs.

For Ross, these conditions have exacerbated an already harrowing living experience, thanks to a disability she developed in her 30s: trigeminal neuralgia, otherwise known as the “suicide disease.” It earns its nickname from the sudden, intense pain in the face it causes, even from activities as mundane as chewing food or brushing teeth, often leading to severe depression in patients. Ross said she’s since had three brain surgeries.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

When CTTU organizers arrived at the complex last October, Ross said that, more than anything else, she felt beaten down and didn’t think she was up for the job.

“I was terrified of it all, even to canvass,” Ross said. But she soon found herself taking action anyway. When the union, the first in Branford, went public in February, Ross was asked to speak at the coinciding press conference. Even though her disability had exacerbated an already lifelong fear of public speaking, she agreed. “When I finished my speech, I broke down. I looked at my daughter and was like, ‘I have no idea what I just said.’ I’m doing things I would never have imagined.”

Echo Maker, too, felt nervous last summer when she was first invited to canvass her building. She decided to bring her daughter along, and said her nervousness evaporated when she saw her daughter’s eagerness to hand out flyers. “This is my job,” her daughter would repeat to herself.

Goldsmith also had to overcome doubts to join the tenant union. In ninth grade, she had to leave school to get a job to help sustain her family; since then, she has been self-conscious about her lack of formal education.

“I get embarrassed sometimes because I don’t spell good,” Goldsmith said. “Sometimes I can’t remember stuff. All my life I knew I wanted to do something good, but what held me back is I was ashamed of my education.”

She recalled one of her first union meetings, at which there was low turnout from her complex. Goldsmith stood up and scolded the organizers for using “big, useless words” that were preventing her and her fellow tenants from fully understanding or engaging. Some were so intimidated that they didn’t come back.

Since then, she said, the meetings became markedly more accessible.

It’s understandable that many tenants have initial hesitations when invited to start organizing, Raghuveer said. After all, the United States does not have a rich history of tenant union organizing and those who are now building out tenant organizations are still figuring out the best strategies for securing safe, affordable housing. That’s part of why TUF launched with only five member unions, planning to expand in 2025—that way it can first assess the effectiveness of collective bargaining, social housing campaigns, electoralism, and rent strikes from its five member unions before expanding further.

Just as these tenants are challenging traditional understandings of leadership, TUF’s efforts are challenging traditional understandings of the housing market. Why should tenants all sign separate leases to live in the same building under the same landlord, when they could all sign one collectively to ensure the contract terms, and fair rents, apply to everyone? Why allow absentee landlords and private equity firms to continue buying up properties just to sell them in a few years, when buildings could instead, through programs like social housing or housing cooperatives, fall under the ownership of those who actually live there and who have a vested interest in the property’s condition? If landlords violate the terms of the contract they voluntarily chose to sign in exchange for tenants’ rent, why should the tenants still be expected to pay? And why can’t a whole building, or a whole union, decide instead to stop?

Even as Raghuveer said the incoming presidency of Donald Trump will present a roadblock in TUF’s existing efforts to campaign to federal agencies like the FHFA, on the whole she said his presidency won’t change the organization’s fundamental strategies or goals.

“This election was about the cost of living, namely the rent, and the missteps the political elites made with the rent and other expenses,” Raghuveer said. “Those material realities that people experience will only be heightened four years from now. That means those problems will all be Donald’s Trump’s problems in four years. The only housing policy he campaigned on was mass deportation, which is certainly not something that will bring the rent down. In four years, the rent will still be too damn high.”

She added, “From our perspective, the enemy is still the same, because the enemy is not a particular party. It is organized real estate.”

No one knows yet how much power tenants can leverage by working together. With no knowledge of an organizing history that could present an alternative, many who have been tenants most of their lives have gotten used to going it alone. When Goldsmith first began organizing, she had trouble breaking through to her neighbors; many had lived in the building for decades, had no hope that conditions would improve or will to fight for them, or just wanted to be left alone. Ultimately, Goldsmith moved out. Hopelessness was a familiar response for Ross and Echo Maker, too, particularly in the moments when their disabilities were most acute.

“I hadn’t done anything for years but survived,” Ross said. “I was a recluse. When I came here, I said to my mom, I feel everybody just comes here to die. Anybody that has been here rarely leaves for a better place. They either go to a nursing home, or are homeless.”

These tenants are bearing the burden of an isolation that comes from a society that pushes low-income, disabled, and elderly tenants to the margins. Just to get into publicly subsidized housing, especially elderly/disabled housing, wait times for vouchers are immense, in some states reaching averages as high as 42 months. Once tenants move in, rent is typically set at 30 percent of their income, with the federal government paying the difference between that sum and “market rent” directly to the landlord. This means that all tenants with these vouchers are cost-burdened—a term denoting tenants spending 30 percent or more of their income on rent—by default. Research has also shown tenants in these complexes are unlikely to relocate.

This all comes as over half the homeless population is over 50 years old and homeless residents in shelters are more than twice as likely to be disabled than the general population.

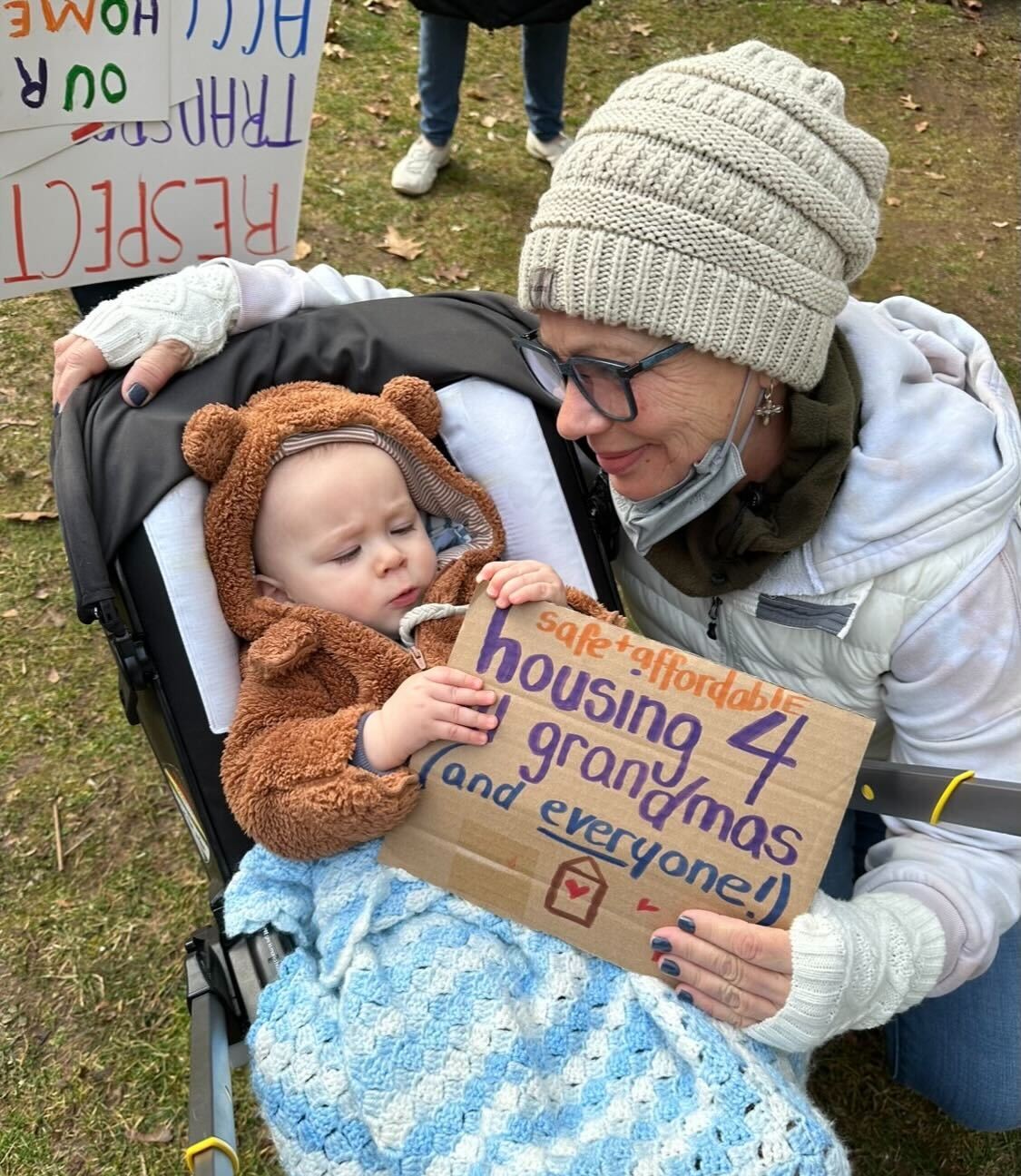

“I hear from tenants all the time in the context of their apartment buildings: I keep my head down,” Raghuveer said. “That is alienating. But the home is such an intimate venue, right? The home is the center of their existence, and so in organizing with their neighbors they forge real connection to one another.” For Echo Maker, the connection comes through the songs they sing at the end of union meetings. For Goldsmith, it’s the fact that the organizer who first knocked on her door is like a son to her now. For Ross, it’s in the way she can bring her 18-month old grandson (“I won’t say no to my grandson, and I feel the same way about the union,” she says) to building-wide barbecues as an unofficial member.

“We’re the front row in each other’s lives,” Ross said. “[The union] gives a sense of belonging. A lot of our residents haven’t had that in a long time.”

The sense of community that tenants who organize together forge becomes essential to their taking bigger risks, like embarking on a rent strike.

On October 1, two TUF-affiliated complexes in Kansas City, Missouri, went on rent strike, demanding not just safe living conditions but also new building ownership, national rent caps, and collectively bargained leases. The participating tenants withheld over $60,000 in rent, and in doing so, have broken their contracts and become vulnerable to eviction (though they argue that their landlords were the first to violate their contract by failing to keep the property in safe condition). Through the entire month of October, though, none of the tenants on strike received eviction notices, and on November 1, an even larger group of tenants at these buildings withheld their rent again, promising to continue until their demands are met.

Evicting one person is easy, if expensive. Evicting a community is hard.

Ross, Goldsmith, and Echo Maker may all have had initial trepidation about organizing and little to no experience. But what ultimately stands out about them is that this hasn’t stopped them from securing victories for the tenant unions anyway.

Goldsmith, for example, recounted getting a call after moving out of her complex from a woman who worked at the health department in Louisville, reaching out as a concerned citizen. A tenant at a local low-income complex had called to report mold problems, and the health department official had seen Goldsmith’s name in the newspaper for the previous tenant union organizing she’d done.

Goldsmith wrote down the building’s address, and in less than two months, she led a majority of the complex to sign union cards.

“This is going to be my legacy,” Goldsmith said. “That’s why I work so hard.”

Ross’s union, meanwhile, was instrumental in pressuring multiple board members of the Branford Housing Authority to resign this year, after holding rallies targeting the board’s public meetings.

On July 25, just 10 months after joining the union, Ross herself was sworn in to fill one of the vacancies, becoming the first housing authority tenant to ever sit on its board.

“To go from leaving these Housing Authority meetings in tears, to having the people that treated us the way they did gone, and me sitting in that position, it’s surreal,” Ross said.

She paused for a moment.

“If you would have said that was possible a year ago, I would have bet my life, no way.”

As these organizers work toward wins on the horizon, they each also spoke about the internal evolutions they’ve undergone, shifting from survival mode to thinking instead about what their survival will have meant for those that come after them.

During my call with Echo Maker, her daughter rushed into the room to show her a new drawing. That’s who she was thinking about when she found out that she’d become, as she puts it, “the first tenant to serve on a federal advisory committee for the nation’s top housing regulator.” And that’s who she was thinking about at TUF’s August launch, where she announced the legacy she’s become so excited to pass on.

“My name is Ozaa Echo Maker. I am an indigenous, disabled, solo parent. I am a leader with Bozeman Tenants United.”

More from The Nation

There is plenty of uncertainty involved in gender-affirming care—as in most aspects of medicine. But the groups behind the Tennessee ban aren’t driven by science—or patient care.

Activists, community leaders, and organizers are already teaming up to prevent LA28 from becoming an echo of the 1936 Nazi Olympics.

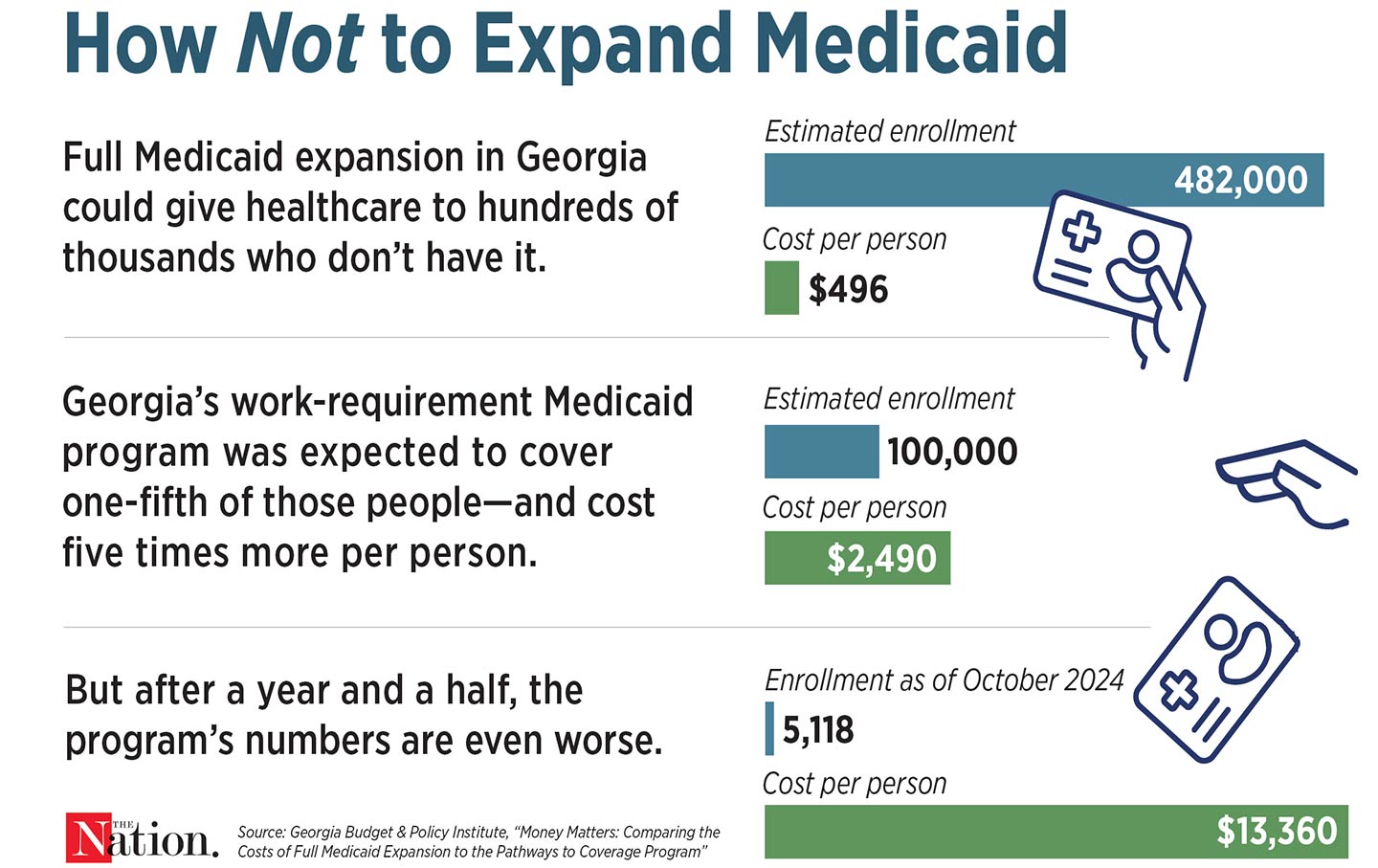

Georgia’s Republican governor, Brian Kemp, said that 345,000 people would enroll in the state’s Medicaid program, which has strict work requirements—so far just 5,118 have.